Agatha Christie wrote her famous detective novel based on an even more famous kidnapping

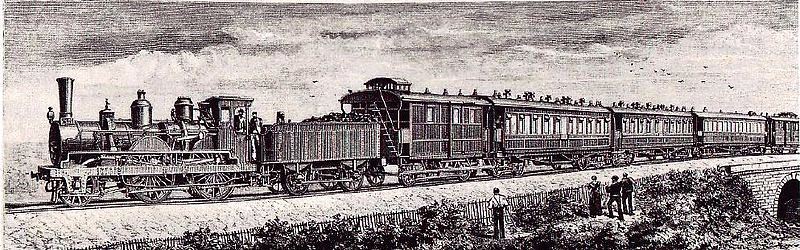

In Agatha Christie’s crime novel Murder on the Orient Express, the well-mustachioed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot solves the grisly stabbing of an American tycoon traveling on a long-distance passenger train. While the 1934 story, adapted for a new movie, of murder and revenge on a stuck, snowed-in train is of course a work of fiction, Christie pulled parts of her story straight from the headlines.

In Christie’s story, Poirot is on the Orient Express, from Syria to London, when a man named Ratchett asks Poirot to investigate the death threats he’s been receiving. Poirot declines, telling Ratchett he doesn’t like his face. The next morning, a snowdrift stops the train in its tracks, and Ratchett is found stabbed to death in his compartment.

When Poirot steps back into his detective role and searches Ratchett’s compartment for clues, he finds a scrap of burnt paper that reads “–member little Daisy Armstrong.” He deduces that Ratchett is really a mobster named Cassetti, who kidnapped the 3-year-old heiress Daisy Armstrong and collected $200,000 in ransom from her parents before her dead body was discovered. A wealthy man, he was able to escape conviction and flee the country. The narrative of the book centers around who on the train murdered Ratchett.

Daisy Armstrong’s fictional case probably rang familiar to readers in the mid-1930s, who had followed national coverage of the kidnapping of the baby son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh. Christie’s official website confirms that the author lifted the idea for the subplot from the true-life tragedy. On March 1, 1932, the 20-month-old child disappeared from his crib. A ransom note affixed to the nursery window of their New Jersey home demanded $50,000.

The Lindbergh kidnapping threw the country into a kind of frenzy. Newspapers literally stopped the presses to break the news for the morning edition. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover mobilized agents to help state authorities in the search. One Hearst reporter, Adela Rogers St. John, recalled in her autobiography: “Remember, little Lindy was everybody’s other baby. Or if they had none, their only child …. Kidnapped? The Lindbergh baby? Who would DARE?”

In both the novel and real life, the children’s bodies were discovered after the ransom was paid in full. Cassetti killed Daisy shortly after kidnapping her, and Charles Jr.’s body was found four miles from the Lindbergh estate; a tree mover had stumbled across a human skull sticking out from a shallow grave. The body had been decomposing there for two months, with a fractured skull and a hole over his right ear.

The book was hugely popular when it was released, and Lindbergh expert Robert Zorn says that the parallels between Daisy and Charles Jr. must have been obvious to people. “The parallels are too striking,” he says. Agatha Christie even had her own insights about the case. She suspected that the kidnapping was done by a foreigner—a hunch proved correct when the culprit was discovered to be German immigrant Richard Hauptmann. “I think she had a better sense of getting to the heart of this than a lot of the investigators,” he says.

Like the novel’s characters, Christie also knew what it was like to be stuck on a train. She loved traveling on the Orient Express and would bring her typewriter along. On one 1931 ride, the train stopped because of a flood. “My darling, what a journey!” she wrote in a letter to her second husband, Max Mallowan. “Started out from Istanbul in a violent thunder storm. We went very slowly during the night and about 3 a.m. stopped altogether.” She was also inspired by an incident from 1929, when the Orient Express was trapped by snow for five days.

The story of the Lindbergh baby captured the popular imagination in a way that a book never could. As Joyce Milton wrote in her biography of the Lindberghs, Loss of Eden, 1932 was a terrifying time. The country was in the throes of the Great Depression, and Hoovervilles were a common sight. World War I, the “War to End All Wars,” hadn’t prevented the creeping rise of totalitarian regimes like fascism and Nazism. Americans couldn’t help but wonder what the world had come to.

Not even the baby of a national hero was safe from kidnappers, and a popular jingle at the time, “Who Stole the Lindbergh Baby?” pondered who would do such a thing.

“After he crossed the ocean wide, was that the way to show our pride?” the song’s lyrics asked. “Was it you? Was it you? Was it you?”

As for Poirot himself, Christie never specified a real-life inspiration for her famous character. However, researcher Michael Clapp believes her Belgian detective might have lived right down the street from her. While looking into his own family history, Clapp discovered that Christie had met a retired Belgian policeman-turned-war refugee named Jacques Hornais at a charity event benefitting refugees from Belgium. It’s not definitive proof, Clapp told The Telegraph, but it’s quite the coincidence.

In the author’s own autobiography, though, she says that Poirot was indeed inspired by one of her Belgian neighbors. “Why not make my detective a Belgian, I thought. There were all types of refugees,” Christie wrote. “How about a refugee police officer?”

Using real-life inspirations for Poirot and Orient Express were far from unusual for Christie. In fact, lots of personal experiences left their mark on her stories, whether it was her knowledge of poisons through her work with the British Red Cross or her fascination with a rubella outbreak that inspired The Mirror Crack’d From Side to Side. Her imagination ran wild, as she wrote in her autobiography, and she didn’t shy away from letting everyday life inspire her.

“Plots come to me at such odd moments, when I am walking along the street, or examining a hat shop,” she wrote. “Suddenly a splendid idea comes into my head.”