Winners of this year’s Land Art Generator Initiative competition proposed beautiful, power-generating works of public art for Abu Dhabi

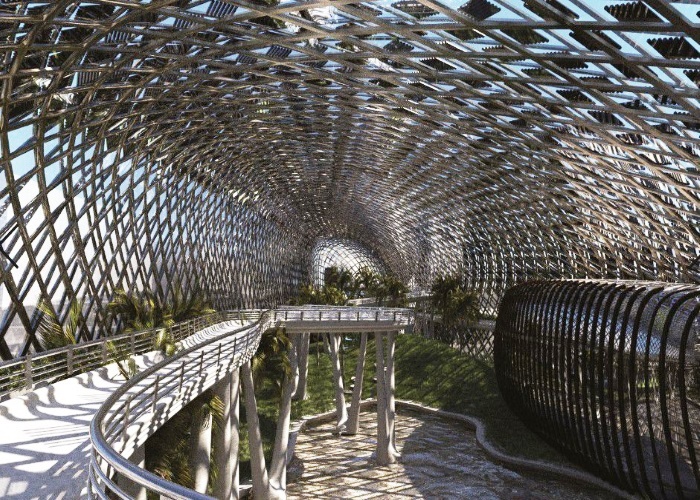

The average high in Abu Dhabi this time of year is nearly 105 degrees. That’s why much of life in the capital of the United Arab Emirates revolves around indoor shopping malls, with their cocoons of artificially chilled air. But imagine walking through an outdoor park beneath a shaded canopy, a light mist cooling your skin. As day turns to night, the light passing through the canopy’s geometric opening makes you feel like you’re strolling beneath the Milky Way.

This canopy concept, designed by New York architect Sunggi Park, is called Starlit Stratus. It’s the winner of a contest sponsored by the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), an organization looking to show that “renewable energy can be beautiful.” Since 2010, LAGI has been hosting a biannual contest for energy-generating public art. Previous contests have been held in places as far afield as Copenhagen, Santa Monica and Melbourne.

This year’s contest took place in Masdar City, a master-planned area within Abu Dhabi that originally aimed to become the world’s first “zero-carbon city.” Though Masdar City has yet to achieve its ambitious goals—it’s still largely empty, and its greenhouse gas emissions are drastically higher than originally planned—the desert provided an inspiring and challenging backdrop for the contest.

“The local climate presented opportunities for solar energy production and the integration of passive cooling strategies to make a comfortable environment year-round,” say LAGI’s founding directors Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry in an email.

Park’s entry was inspired by origami tessellations. It’s composed of triangular solar panels to generate energy during the day and triangles of fabric that can be unfolded at night. It’s set on telescoping columns to allow for height adjustments, so it can capture the shade as the sun moves across the sky. Excess energy accumulated by the solar panels is used to collect moisture from the air, which can be stored as drinking water or used to provide a cooling mist.

“What impressed the judges about this project is the pragmatic approach to maximizing solar surface area in a manner that radically and dynamically transforms public space,” say Monoian and Ferry.

Park first learned origami as a kindergartener. “I loved the fact that a thin paper could turn into any geometry,” he says. “[The] origami that I learned when I was a kid influenced the LAGI competition.”

For their win, Park and his team will receive a cash prize of $40,000.

“I never expected I’d win this competition,” Park says. “I feel honored and grateful.”

The second-place winner was a project called Sun Flower, from Ricardo Solar Lezama, Viktoriya Kovaleva and Armando Solar of San Jose, California. It’s an enormous abstract flower sculpture with solar panel “petals” open in the day to collect energy and provide shade. At sunset, the petals gently close, their weight generating more energy. This energy illuminates the sculpture through the night like a giant lantern.

Other projects include a solar paneled sundial, a solar panel-topped labyrinth, and a rainbow-colored canopy to provide the city streets with colorful shade. One project uses house-size spheres painted with Vantablack (a material that absorbs 99.96 percent of visible light) to absorb sunlight. When night falls, the stored solar energy is used to inflate an even bigger white sphere that serves an event venue or communal gathering space. Many of the projects took inspiration from Emirati culture—one incorporates calligraphy, another plays with the concept of the desert oasis, while another features enormous “falcon eggs” made of solar panels, a nod to the national bird.

Monoian and Ferry hope to turn many of LAGI’s 1,000-plus entries into reality. Several are currently in progress, they say.

“We hope that LAGI can inspire people and instill a sense of desire and wonder for a new and better world that has drawn down carbon emissions to zero—to see what that world looks like and imagine themselves there,” they say. “After all, that is the world we must create for ourselves by 2050 at the very latest.”