In 1979, the new device forever changed the way we listened to music

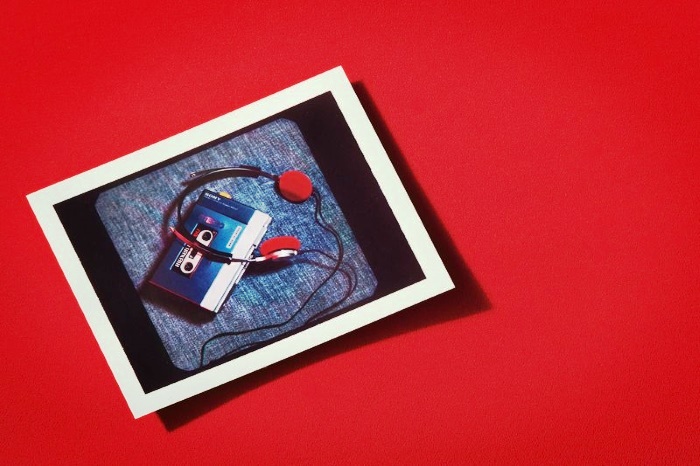

In 1979, when Sony introduced the Walkman—a 14-ounce cassette player, blue and silver with buttons that made a satisfying chunk when pushed—even the engineers inside Sony weren’t impressed. It wasn’t particularly innovative; cassette players already existed, and so did headphones. Plus, the Walkman could only play back—it couldn’t record. Who was going to want a device like that?

Millions of consumers, it turns out. The $200 device—over $700 in today’s money, as pricey as a smartphone—instantly became a hit, selling out its initial run of 30,000 in Japan. When it went on sale at Bloomingdale’s in New York City, the waiting list stretched to two months. (An early version of the Walkman now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.)

What was the allure? The sudden portability of gorgeous, head-filling sound. Previously, if you wanted to hear hi-fi music on headphones, you were stuck tethered to a home stereo. The Walkman unmoored you. Now you could walk down the street, and the music altered the very experience of looking at the world. Everything—the pulsing of traffic, the drift of snowflakes, passers wandering by on the sidewalk—seemed laden with new meaning.

“Life became a film,” as Andreas Pavel, an inventor who’d patented his own prototype of an ur-Walkman, years before Sony, once noted. “It emotionalized your life. It actually put magic into your life.” Or as one 16-year-old Walkman wearer described it in historian Heike Weber’s account, “I have my own world, somehow. I see it differently and hear it differently and feel stronger.” People used the Walkman to help manage their moods and calm stress; dentists would plop Walkman headphones on a patient before drilling. Andy Warhol tuned out the din of Manhattan: “It’s nice to hear Pavarotti instead of car horns,” he said.

The device also became a fashion statement, a badge of modernity: Sony’s ads portrayed a roller-skating couple joyfully sailing along, Walkman held aloft. For the first time, sporting a piece of cutting-edge hardware was fashionable, not dorky.

“It was the first mass mobile device,” notes Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow, author of Personal Stereo. “It changed how people inhabited public space in a pretty profound way.” It paved the way for acceptance of the mobile phone, today’s truly omnipresent portable tech.

But, much like the mobile phone, the Walkman tore a rent in the social fabric. To use one was to intentionally seal the public out. “It’s the privatizing of space,” Michael Bull, a University of Sussex professor, who studied Walkman users in the ’90s, told me. “Personal stereos are visual ‘do not disturb’ signs,” he wrote in his book Sounding Out the City. Earlier transistor radios, which had single earpieces, didn’t have that effect. “The experience of listening to your Walkman is intensely insular,” as the music critic Vince Jackson wrote in the British magazine Touch. “It signals a desire to cut yourself off from the rest of the world at the touch of a button. You close your eyes and you could be anywhere.” Bull, for his part, said listening to a Walkman was healthy, a kind of assertion of autonomy.

Plenty disagreed. To them, it seemed fantastically rude: “Our marriage or your Sony,” as graphic designer James Miho’s wife warned him in 1980, after, as the New York Times reported, he tuned her out for reggae. The philosopher Allan Bloom, in The Closing of the American Mind, inveighed against the specter of a boy doing his homework with a Walkman on, “a pubescent child whose body throbs with orgasmic rhythms”—a generation of kids cut off from great literature: “As long as they have the Walkman on, they cannot hear what the great tradition has to say.”

Soon enough the Walkman was a symbol of navel-gazing self-absorption. Critics mocked narcissistic yuppies for listening to self-help books on their commutes to upscale jobs, and derided GenX slackers for lethargically dropping out, sitting in an emo trance. “A technology for a generation with nothing left to say,” Der Spiegel reported.

“You couldn’t win, no matter how you used it,” Tuhus-Dubrow laughs.

Interestingly, Sony itself was worried the machine encouraged antisocial behavior. Sony’s boss, Akio Morita, ordered that the first Walkman include a second headset jack—so two could listen at once. But it turns out nobody wanted it. “People wanted to listen by themselves,” Tuhus-Dubrow notes.

Yet people did indeed create a vibrant social culture around the Walkman. They shared earbuds; they made mixtapes for friends or dates. Indeed, making mixtapes—stitching together songs from one’s home stereo, to make a new compilation—became a distinctly modern activity. The message was not in any one song but in their combination, their sequencing. “Mixtapes mark the moment of consumer culture in which listeners attained control over what they heard, in what order and at what cost,” as the critic Matias Viegener wrote. Mixtapes also helped fuel the panic over copyright, with the music industry launching a campaign claiming that “Home Taping Is Killing Music.”

It didn’t kill music, of course. But gave us a glimpse of our coming 21st-century world—where we live surrounded by media, holding a device in our hands at all times.