In 1855, Mary Mildred Williams energized the abolitionist movement

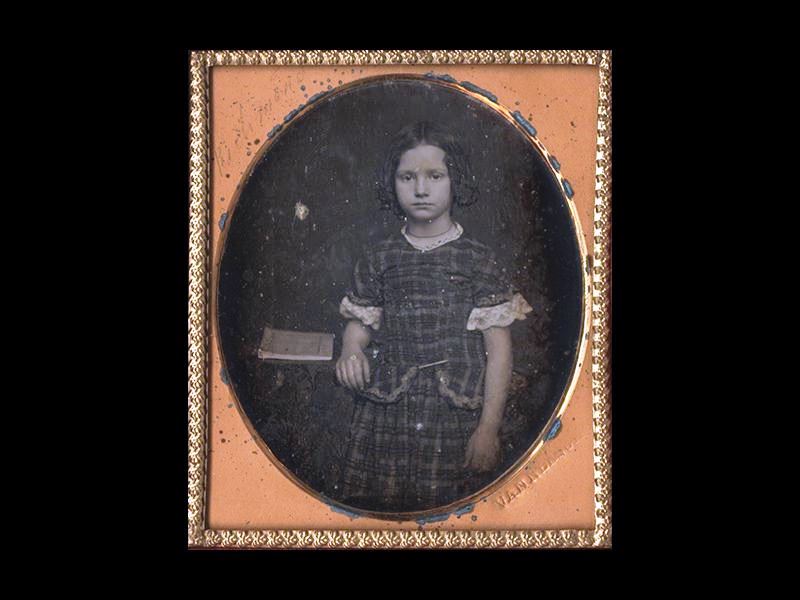

On February 19, 1855, Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator, wrote his supporters about an enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. She would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring. “I think her presence among us (in Boston) will be a great deal more effective than any speech I could make,” the noted orator wrote. He said her name was Mary, but he also referred to her, significantly, as “another Ida May.” Sumner enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. She is neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, and looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

When the Boston Telegraph published Sumner’s letter, it caused a sensation. Newspapers from Maine to Washington, D.C. picked up on the story of the “white slave from Virginia,” and paper copies of the daguerreotype were sold alongside a broadsheet promising the “History of Ida May.”

The name referred to the title character of Ida May: A Story of Things Actual and Possible, a thrilling novel, published just three months earlier, about a white girl who was kidnapped on her fifth birthday, beaten unconscious and sold across state lines into slavery. The author, Mary Hayden Green Pike, was an abolitionist, and her tale was calculated to arouse white Northerners to oppose slavery and to resist the Fugitive Slave Act, the five-year-old federal law demanding that suspected slaves be returned to their masters. Pike’s story fanned fears that the law threatened both black and white children, who, once enslaved, might be difficult to legally recover.

It was shrewd of Sumner to link the outrage stirred by the fictional Ida May to the plight of the real Mary—a brilliant piece of propaganda that turned Mary into America’s first poster child. But Mary hadn’t been kidnapped; she was born into slavery.

I first learned of Mary in 2006 the same way the residents of Boston met her in 1855, by reading Sumner’s letter. That chance encounter led me on a 12-year-long quest to discover the truth about this child who had been lost to history, a forgotten symbol of the nation’s struggle against slavery. Now the true story of Mary Mildred Williams can be told in detail for the first time.

In the reading room of the Massachusetts Historical Society, I held Mary’s daguerreotype, labeled “Unidentified Girl, 1855.” She would still be missing but for a handwritten note offering a clue to her identity: “slave child in which Governor Andrew was interested.” I went on to find the story of Mary and her family in thousands of documents spread across 115 years, beginning in the court filings and depositions of the Cornwells, the Virginia family who had owned Mary’s grandmother, Prudence Nelson Bell, since 1809. Prudence and her children were all so light as to “be taken to be white,” the courts stated. Their skin color was evidence of a then-common act: nonconsensual sex between an enslaved woman and a white member of the master class. Mary’s mother was Elizabeth, Prudence’s daughter with her mistress’s neighbor, Capt. Thomas Nelson. Mary’s father was Seth Botts, an enslaved man who was the son of his master. Elizabeth and Seth were married in the early 1840s. Mary, their second child, was born in 1847.

In 1850, Mary’s father escaped to Boston via the Underground Railroad, changing his name along the way to Henry Williams to match his forged free papers. Through his remarkable charisma, Williams raised enough funds to buy the freedom of his children, his wife, her mother and four of Mary’s aunts and uncles. Abolitionist John Albion Andrew—the future governor of Massachusetts—was Williams’ lawyer, and he contacted Sumner to handle the funds needed to redeem Mary and her family from Virginia. Once freed, they traveled to Washington, where they met the senator.

Sumner said the oldest Williams child, Oscar, was “bright and intelligent, [with] the eyes of an eagle and a beautiful smile.” But Sumner chose to photograph Mary and introduce her to journalists and Massachusetts legislators. Oscar was dark, like his father, while Mary was light, like her mother. Mary’s whiteness made her compelling to white audiences.

Throughout the spring of 1855, Mary made headlines in Washington, New York and Massachusetts. In March, she sat onstage at Boston’s Tremont Temple as Sumner lectured to a crowd of thousands. And at least twice she appeared with Solomon Northup, a free-born black man who had, in fact, been kidnapped and enslaved; he had told his story in his memoir Twelve Years a Slave.

“Little Ida May” faded from view after the Civil War, but I was able to piece together the basic facts of her life. She never married and did not have children. She resided mostly in Boston, near her family, working as a clerk in the registry of deeds and living as a white woman—a decision criminalized in the Jim Crow era as “passing.” The Rev. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an abolitionist who knew her, said he “willingly lost sight of her” so she could “disappear…in the white ranks.” Mary moved to New York City in the early years of the 20th century; she died in 1921 and her body was returned to Boston and buried with her family in an integrated cemetery. I never found a single letter or document written by Mary herself, and no contemporary quotation of hers survives. Her own voice remains unheard.

In March 1855, young Mary was taken to the offices of the New-York Daily Times, where reporters looked her over and expressed “astonishment” that this child was “held a slave.” Today, people are similarly surprised when I show them the daguerreotype of Mary and I point out she was born into slavery. They react the same as people did a century and a half ago, revealing that they still harbor some of the assumptions about race and slavery that Sumner tapped into when he first put Mary onstage.