The dime novels and story papers entertained boys and launched a popular culture we still consume today

In the early evening dark of March 30, 1889, a thick crowd of eager children – estimates say as many as 2,000 – converged on the Palace Rink in Brooklyn for the inaugural Convention of the Golden Hours Club.

Golden Hours, a popular “story paper” full of adventure stories for young readers, had prepared a jam-packed evening of entertainment for its fans: peppy, patriotic songs descended from an orchestra couched in the music loft. The children were treated to hours of performance from musicians, Civil War veterans, ventriloquists and caricaturists, with the itinerary running until nearly midnight. There were celebrities, too: the author Edward Ellis talked at length to a rapt crowd about “the Indians, of whom the boys have read so much.” The kids, noted the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “were noisy and hearty and were afforded full rein.”

The keynote speaker was no less than circus mogul P.T. Barnum, who at 79 years old could still leave a crowd hanging on his every word. “When the rotund form and curly gray locks of the venerable showman appeared inside of the door,” wrote the Eagle’s correspondent, “the youngsters arose to their feet and cheered and stamped and whistled.” The New York Times corroborated, claiming that the roaring and cheers of the assembled children were louder than any circus calliope, and that “Barnum never got a more honest ovation.”

Giving the children high-fives and handshakes, Barnum waited five minutes for the applause to subside, at which point he did a few magic tricks for the crowd, pulling a half-dollar from one volunteer’s nose. When he spoke, it was to advocate for moral living and the importance of good habits, and he warned the children against tobacco and alcohol: “We are all made up of a bundle of habits….The boy who smokes a cigarette does more than nature intended he should do, and the girl who wears cheap jewelry is trying to make 2 and 2 equal 22.”

The late 19th century was a fertile period in America for popular literature, in large measure due to the rise of pocket-sized dime novels and weekly illustrated “story papers” of serialized popcorn fodder that plainly and spryly catered to the public taste, asserting the newly prominent role of the audience as a driver of mainstream American culture. This phenomenon, of course, was nothing new to Barnum, who had for decades built a thriving career on his ability to shape and evolve with popular taste.

These periodicals were printed cheaply and often, and thanks to their low price and a rising literacy rate they were wildly popular, creating the space for a direct line – from both a writer’s and an audience perspective – into modern popular fiction, particularly in the fan-friendly comic, fantasy and sci-fi genres.

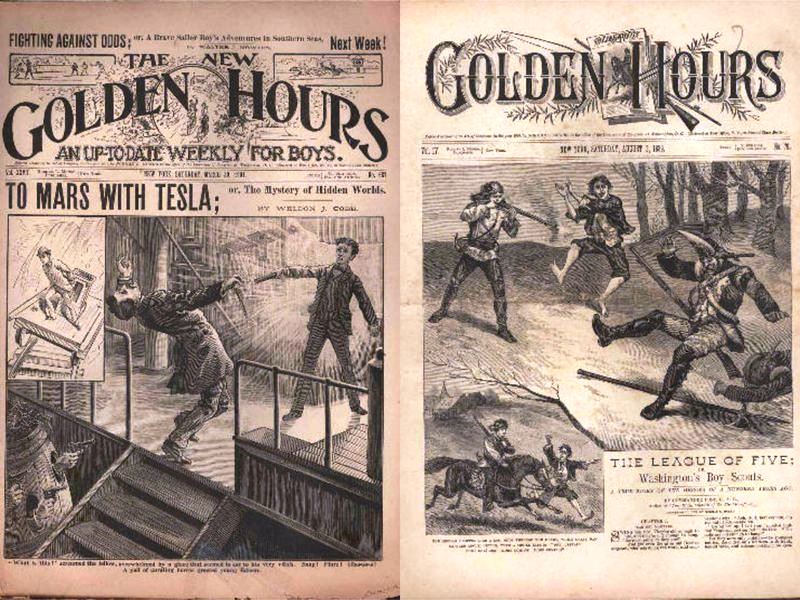

Hundreds of titles appeared from the Civil War period onward, among them Frank Leslie’s Boys of America, Pleasant Hours for Boys and Girls, and Beadle’s Dime Novels. Golden Hours was one of the most popular story papers, printed weekly from 1888 to 1904 in more than 800 issues. The paper generally featured, as most story papers did, episodic action stories that nurtured nostalgia for the glow of pre-industrial frontier America: one issue from April 27, 1889, contains a very typical tale titled The Adventures of Two Boys Among the Utes: A Stirring Story of Hunting and Indian Adventure. Men and boys in story papers (and they usually were men and boys, unfortunately, leaving the female experience in flimsy supporting territory if not omitting it entirely) trafficked in rugged adventure: adventure at sea, on the prairies, with hostile Indians, in the jungle, around the campfire. Native people were presented in particularly unfriendly light, usually represented as shallow, animalistic savages whose presence in the plot served mainly to justify their own extinction. This preference for stereotype was evident from the beginning: the first so-called “dime novel,” Ann Stephens’ Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter, includes the protagonist’s belief that “that the ravine was full of concealed savages, who would fall upon him like a pack of wolves.”

Story papers were not simply thrilling, but, in a particularly modern sense, participatory. The papers featured regular contests, puzzles, Q&A features and letter columns, and provided a venue in which children could, for a time, feel independent: grown-up enough to purchase and read their own paper, kids could interact with editors by submitting letters or stories of their own, share a common experience with other readers and even suggest where the story might go next. Children could not only write letters or take part in contests, but submit their own writing for a shot at seeing their name in print. One contest even asked young readers to write up an adventure from their own lives, and submit a re-created photograph to go with it. Author Sara Lindey calls these story papers a means by which boys could “write themselves into adulthood.”

An author in the 1918 issue of Writers Monthly fondly recalled the formative impact of the story papers and their literal cliffhangers on his generation, then grown with children of their own and “much too old to feel, any longer, the gnawing anxiety which overwhelmed us when one of these six writers left his hero hanging by a cliff ‘a thousand feet above the valley’ for six whole days, and Saturday came around again and we could get the next number and find out how he was rescued.”

Though many parents worried that low-art dime novels would indeed mean trouble in River City, in many cases these publications attempted not only to entertain their young audience, but to teach the upright moral values that would come to characterize “muscular Christianity” in America, a philosophy that drew on the New Testament to suggest that, particularly for young men, physical health and moral character were linked (the YMCA and the late-19th century rise of American football are also closely linked to this manly ethos). The story papers usually glorified American frontier spirit, fresh air and a certain beefy, freshly-scrubbed masculinity.

Barnum himself was an early progenitor of melding America’s religious undercurrents with popular culture, devising what we today would consider “family” entertainment, by weaving through his productions an agenda driven by Universalist Christianity and the American temperance movement. Around the time of the convention, Barnum was not only enjoying the fame brought to him by his circus, now 18 years old, but was well into a new career as a children’s author, writing animal and adventure stories to keep his name fresh before the evergreen youth of America.

Barnum biographer Arthur Saxon notes that, while it is evident that Barnum was a good writer and readily able to adapt his style to children, most people assume that he engaged in a very modern celebrity convention and was helped by a ghostwriter to produce books like Lion Jack and Dick Broadhead, a Tale of Perilous Adventures. In The Wild Beasts, Birds and Reptiles of the World, Barnum acknowledges ‘my friend Edward S. Ellis, A.M., for his help in the preparation of these pages.’” (Perhaps even more tantalizing, the rise of Barnum’s career as a YA author handily coincides with his marriage to his second wife Nancy Fish, who was a skilled writer and would eventually publish under her own name.)

Name-dropping Edward S. Ellis was a big deal: Ellis was a titan of Gilded Age youth literature, and his 1868 robot novel The Steam Man of the Prairies is often considered to be the first American work of “edisonade,” a modern term that refers to stories about clever, young, steampunk-y inventors. In Ellis’ story, characters described only as an “Irishman” and a “Yankee” stumble upon a teenager who has ingeniously built a steam-powered robot to pull a carriage for him. (Adventure!) The robot, cutting-edge and thoroughly alien, is ten feet tall, stout, and vaguely menacing with a tin stovepipe hat and a glowing coal furnace in its stomach.

So when the Golden Hours Club – a nationwide fan club of some 10,000 members set up by the paper’s publisher – decided to hold their first-ever fan convention, putting P.T. Barnum alongside Edward Ellis onstage was the 19th-century equivalent of saying you’d have Stan Lee and George R.R. Martin appearing together at Comic-Con.

Dime novels continued solidly in production into the 1920s, at which point radio and pulp magazines had become the audience go-to for exciting fantasy and fiction. But fan conventions continued: by the 1930s, there were gatherings for radio enthusiasts, circus fans and sports buffs (many sporting events were themselves referred to as “fan conventions”).

The robust fan culture of the later 19th century was an early indicator of how interactive fandom would become, and how much it would depend on empowering consumers, particularly young ones. Fan conventions today – which number in the hundreds of thousands of people in annual attendance – depend on the very same mix of celebrity, storytelling and the invitation to join in the active pursuit of lived fiction.