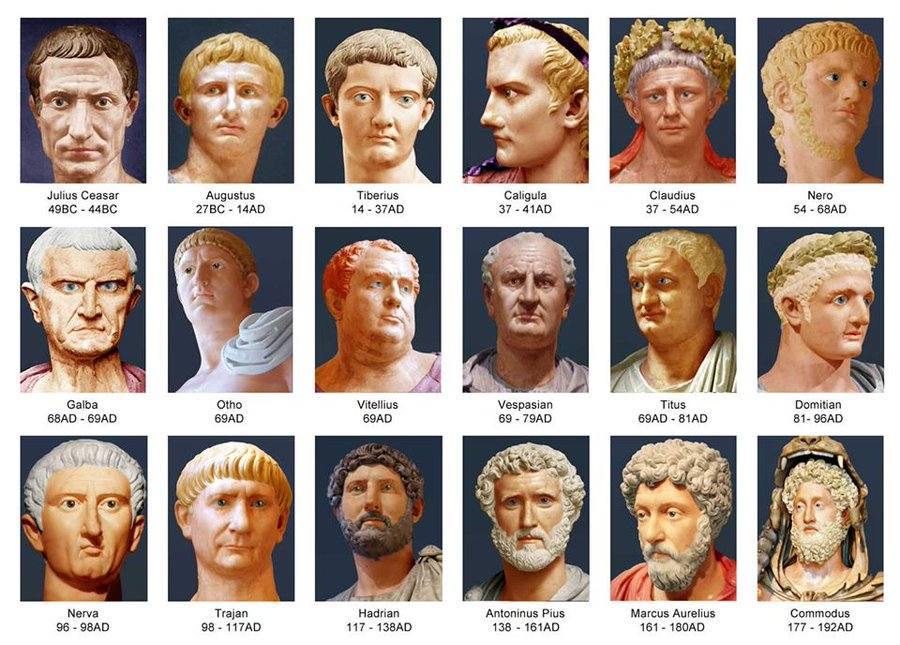

The Romans painted their statues – this is reasonably close to how they would have looked in the emperors’ lifetimes. The hair and eye colors are taken from ancient Roman descriptions.

Artists in classical cultures such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome were known to paint with a variety of hues — a practice known as polychromy (from Greek, meaning “many colors.”) So why do wealways think of antiquities as colorless?

The myth of the white marble started during the Renaissance, when we first began unearthing ancient statues. Most of them had lost their original paint after centuries of exposure to the elements, and contemporary artists imitated their appearance by leaving their stone unpainted.

The trend continued into the 18th century as excavations brought more and more artworks to light. That’s also when Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who many consider the father of art history, literally wrote the book on ancient art, framing our modern view of it. Although he was aware of the historical evidence that sculptures were once colorful (some discoveries even had some paint left on) he helped idolize whiteness.

“The whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well. Color contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty. Color should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not (color) but structure that constitutes its essence,” he wrote.

But for over a decade, “Gods in Color,” a traveling exhibition whose main findings have been collected into a book, has offered the public a chance to see these statues as the ancients would have seen them, staging precisely rendered, full-color reproductions.

“This exhibition introduces the message that sculptures were painted often with dazzling and garish colors, with reconstructions of what they might have looked like, based on the colors and pigments that were available at the time,” Renee Dreyfus, a curator for the exhibition, said in a phone interview.

Looking for “paint ghosts”

The research of Vinzenz Brinkmann, an archeologist and professor at Frankfurt’s Goethe University, coalesced in the original “Gods in Color” show at Munich’s Glyptothek museum in 2003

To create reproductions, Brinkmann starts by simply looking at the surface of the sculptures with a naked eye, before adding various visual aids in the form of ultraviolet of infrared lamps. The light source must come from a very low angle, nearly parallel to the surface being analyzed. That simple trick brings out details otherwise impossible to see.

Because paint acts as a coating and wears off unevenly, bits of surface that were covered in paint will stand out as they were protected from erosion.

“That can show a variety of different paints that are there or are gone, but have left a paint ghost,” Dreyfus said.

This “paint ghost” can help researchers deduce the original paint patterns on the statue. It can also help in understanding what types of pigments might have been used, as more resistant ones would have lasted longer than weak ones.

“We can also grind minuscule amounts of the original pigment, where present, and determine what its color was,” Dreyfus said.