When current excavations at Pompeii unearthed the remains of a seemingly decapitated skeleton, an image was released by archaeologists working in Regio V. Thought to be of a man crushed by an enormous door jamb while attempting to flee the deadly Vesuvian eruption of 79AD, the image was widely shared, in many cases with the addition of captions which poked fun at the Pompeiian’s dramatic demise.

Yet the photograph is essentially a representation of human remains – a snapshot of the circumstances of someone’s death – raising questions as to the ethics of the “meme-ification” of the dead and our own often abstract perception of death and dying.

Death in the contemporary age has become a concealed, obscure and managed process – largely confined to the remits of hospitals, care homes and funeral parlours. Yet one sphere in which we more readily confront death is that of the museum. Pompeii is one archaeological site which immediately conjures up deathly narratives for the general population, with the site and its surrounds attracting an estimated 4m visitors each year. A ticketed exhibition at the British Museum in 2013 was seen by more than 471,000 visitors and was the third most visited exhibition in the museum’s history after Tutankhamun and the Chinese Terracotta Army.

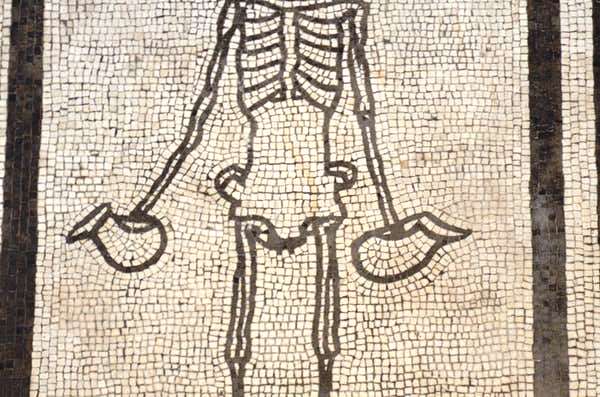

While the unfortunate Pompeiians may not have known that they were destined to meet their end by eruption, they did accept – and celebrate – that they were going to die. One particular mosaic from a residential reception room from Pompeii (now housed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum) expresses this ideology in its playful depiction of a single skeleton, which smiles out at you with two askoi (jugs) in hand.

This mosaic – like examples elsewhere – was located on the floor. They were the literal and metaphorical grounding on which the festivities, spontaneities and indulgences of Roman life played out. And their message, however macabre, was simple: drink up! Be merry! As death waits for us all …

With their morbid message, remember you will die, these early memento mori, along with their many counterparts in 17th-century art, might not initially seem relevant to contemplations of death in the modern day. Yet we use – or perhaps abuse – their direct descendant in the digital age, with this particular perspective on life and death hidden in a hashtag: #YOLO.

You only live once – a realisation that life is fleeting and death is certain. Whether that last drink, a first date or parachuting off buildings, the message is similar: embrace the risk, put your already condemned bodies on the line, subscribe to a Nike-like philosophy of life and “just do it”.

Modern memento mori

Whether a smiling skeleton or status update, these statements of defiance in the face of death acknowledge its very inevitability. Yet another movement is working to further the message of memento mori in their acceptance of death as an integral and visible part of life with an arguably more meaningful purpose.

The Death Positive movement does not – unlike Roman decorators or certain twitterati – encourage the excessive consumption of alcohol or the performance of potentially dangerous stunts in the knowledge that the physical bodies which we are will inevitably cease to function. But it does advocate for using our present, living lives as an opportunity to discuss and make clear our wishes for their eventual end. It argues that such dialogues are not morbid but natural and necessary and that the “culture of silence” surrounding death in the modern era needs to be broken.

More than a thousand years before the active development of death positivity then, the mosaics of doomed Pompeii were directly echoing the main tenets of the modern movement’s manifesto: know you are mortal, know you will die and know you should act accordingly.