In the 1960s, a group of young art students upended tradition and vowed to show their real life instead

For young artists far from home, the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the mid-1960s must have been a heady scene. They came from all across the United States, many still in their teens, from small towns, cities and reservations. One of them, Alfred Young Man, a Cree who arrived there from a reservation in Montana, later remembered the students speaking 87 different languages. It was “a United Nations of Indians,” he wrote.

The school put rich stores of art materials at the teenagers’ disposal and let them loose. They blasted Rock ’n’ Roll and Bob Dylan late at night in the art studios. They gathered at a girls’ dorm to eat homemade frybread. They painted and sculpted, performed music and danced. They studied centuries of European, American and Asian art, and they debated civil rights and Pop art. Their instructors, Native and non-Native alike, urged them to embrace and share their varied cultural backgrounds.

The artwork that grew out of that environment was groundbreaking, says Karen Kramer, curator of “T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America,” a show dedicated to one of those artists, which is now at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Heye Center in New York City. Cannon, a painter and writer, along with peers like the painters Young Man, Linda Lomahaftewa and Earl Biss, the ceramicist Karita Coffey and the sculptor Doug Hyde, were among the first to express a strong Native American point of view through the ideas and methods of cutting-edge contemporary art. Together, Kramer says, “they changed the look and feel of Native American art.”

In the early part of the 20th century, even supporters of Native American art had thought it should be sheltered from external artistic influences, as a way of preserving it. The work was dominated by flatly representational drawings and watercolors depicting traditional rituals, deer hunting and the like. In the late 1950s, scholars and Native American artists met at the University of Arizona to discuss how to revitalize the art. They proposed something that at the time seemed radical: giving some of its rising stars the same kind of art education available to non-Native art students. The group’s proposal raised what it called a “puzzling question”—whether Native students would even “benefit from association with non-Indian concepts, art forms and techniques.” Fortunately for T.C. Cannon and his cohort, the proposal went forward, and eventually, in 1962, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs opened IAIA.

Early on, the IAIA students “decided they were not going to be the kind of artists their forebears were,” says Mike Lord, who although not a student there, was close friends with Cannon and others. They called the earlier generation’s work “Bambi art,” he says. As Cannon later put it, “I am tired of Bambi-like deer paintings reproduced over and over—and I am tired of cartoon paintings of my people.” Lord says the students took an “almost in-your-face” pride in “doing things that hadn’t been done before.”

Kramer attributes the school’s strength to the esteem it constantly espoused for Native culture—a culture that the U.S. government had spent decades trying to crush. Some of that “cultural trauma,” Kramer says, had been shockingly recent: many IAIA students’ parents would have attended mandatory government-run boarding schools that banned their languages, dress, religious practices, hairstyles and even names. Their grandparents might have been forcibly removed from their land. “If you’ve grown up [being] made to feel ashamed of [your] cultural background and pressured to assimilate,” she says, then to arrive at a school that encourages “putting your cultural heritage up front and being proud of it is a really big pivot.”

Instructors at IAIA were accomplished artists and active in contemporary art world of the time. One had studied with the Bay Area figurative artist Wayne Thiebaud, another with the influential abstractionist Hans Hofmann in New York. “This confluence of the quality of the instructors, the energy and sharing of students that was encouraged, the political energy surrounding the 1960s and ’70s [and] the Civil Rights movement,” Kramer says, all combined to make IAIA a place of highly productive ferment.

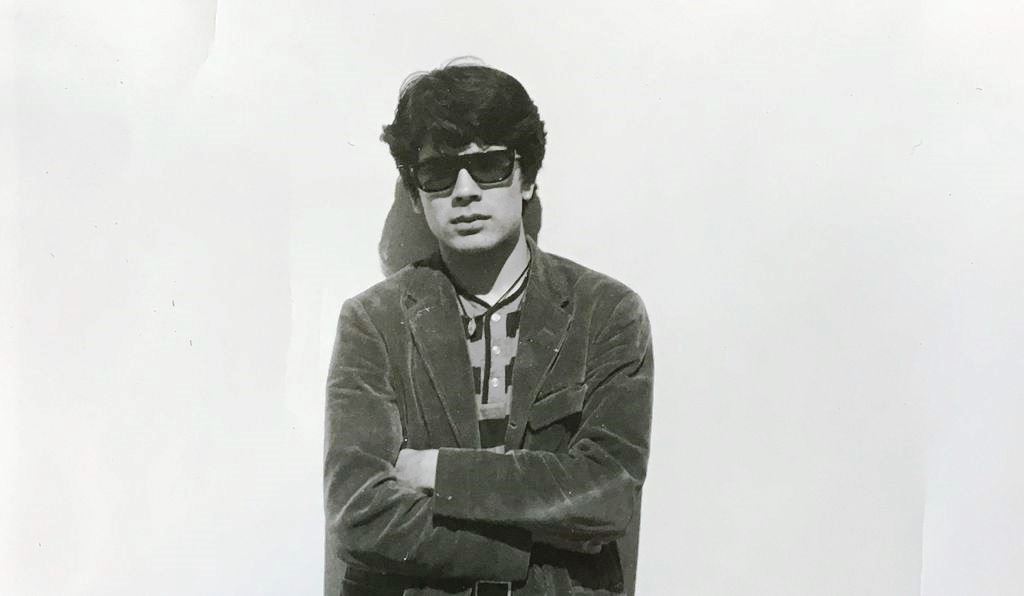

T.C. Cannon, who died in a car crash in 1978 at age 31, was a multimedia talent. The exhibition in New York combines dozens of his paintings, drawings and prints along with his poems and song lyrics printed on the walls. (It opened last year at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, where Kramer is curator of Native American and Oceanic art and culture.) The show also includes a recording of Cannon singing one of his own Dylan-inspired songs, as well as letters and artifacts, such as the two Bronze Stars he earned in the Vietnam War, where he spent almost a year with the 101st Airborne Division.

Cannon had Caddo and Kiowa ancestry and grew up in rural southeastern Oklahoma. He arrived at IAIA in 1964, the year he turned 18. He grabbed the chance to study the European masters, drawn especially to Matisse and van Gogh, along with the contemporary Americans Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

His painting Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues, which he painted while still a student, shows Rauschenberg’s influence, Kramer says, with its layered images and text. It presents an older couple wearing a combination of traditional Navajo dress and trendy dark sunglasses, poised between history and modernity.

Almost all of Cannon’s large paintings are portraits, often in electric shades of orange, purple and brilliant blue. Many vividly depict Native Americans as living, sometimes flawed individuals. His figures have pot bellies, wide hips or skeptical expressions, and one of them slouches in a folding lawn chair. But they are still here, they seem to say, surviving and even flourishing—not decorative stereotypes but people getting by in the modern world.

Cannon made several smaller images depicting George Custer, the U.S. Army commander whose “last stand” was a resounding victory for Native American forces fighting a move to drive them off their land. In an untitled portrait of Custer made out of felt, the word “Ugh?” rises from his head in a cartoon thought bubble, as Cannon seems to ask dryly how this guy ever emerged as an American hero.

“What was key about T.C. was how he appropriated certain moments [and] characters in American history, but from an indigenous perspective,” Kramer says. “He was doing it with a wry humor, and he was borrowing the visual language of the oppressors and using it as a platform to explore Native identity [and] Native history.”

Between his “natural talent at painting people” and his sunshine-bright colors, Kramer says, his images pull viewers in. “As human beings, we’re drawn to other human beings on canvas.” Portraiture, she says, was “a really useful tool” for Cannon in focusing on the uncomfortable topics he wanted to bring to the fore. “So many issues he was grappling with in the 1960s and ’70s”—freedom of religion, ethnic identity, cultural appropriation—“are still so relevant.”