While the movie has been critiqued for flattening the legacy of Queen, see the band come to life in historic photos

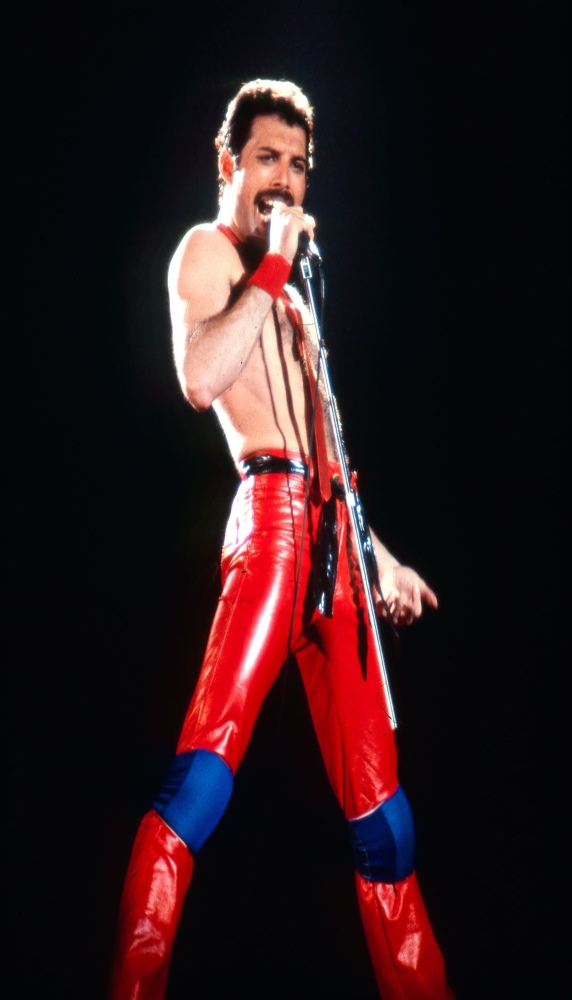

Bohemian Rhapsody will probably not rock you if film critics have anything to say about the new Queen biopic that sees Rami Malek tug on the tight leather pants of Freddie Mercury, the band’s brilliant, frenetic, hedonistic lead singer, who brought a new intensity to what rock ’n’ roll music could be.

The movie tells the story of the inception of Queen in the early 1970s up through its heart-pounding 20-minute set at the Live Aid concert in Wembley Stadium in 1985. But the film has already been slammed for being perceived as caring more about telling a crowd-pleasing story than really digging into Queen’s legacy.

“A baroque blend of gibberish, mysticism and melodrama, the film seems engineered to be as unmemorable as possible,” writes A.O. Scott in a scathing review forThe New York Times. It’s “safe and circumspect,” writes Glen Weldon for NPR. “It’s a bizarrely anodyne film, too feel-good to be convincing,” writes Amanda Petrusich for the New Yorker. Over at Rolling Stone, Andy Greene helpfully offers a fact-check guide to the scenes the movie gets historically inaccurate (no, the band did not break up before Live Aid).

The problem, as with most biopics, lies squarely with the flattening of history, in this case Mercury’s. It’s been more than 25 years since the Queen frontman—born Farrokh Bulsara in the then-British colony of Zanzibar—died of complications from AIDS in 1991. While his onstage persona is the focus of the film, his “considerable appetites” as Petrusich of the New Yorker puts it, are barely touched upon— “a coffee table smeared with cocaine, a loaded glance outside a truck-stop toilet, a late-night goose,” that’s all, she writes.

In Into, an LGBTQ-focused digital magazine, Juan Barquin calls attention to the missed opportunity in Bohemian Rhapsody to explore Mercury’s bisexuality, attributing the gloss over in the fall release to its rating, which is PG-13, “and the fact that the surviving straight members of Queen had too much of a hand in telling a dead queer man’s tale.” (Queen’s original guitarist, Brian May, and drummer, Roger Taylor, are listed as executive music producers for the film.)

Calling the movie a sympton of a larger issue at play for how Mercury’s legacy is told today, Barquin argues the problem “lies in the way history has chosen to remember him, simply as a flaming frontman or as a gay man, bisexuality erased and deeper looks into his life left in the shadows.”

That’s the point that Lakshmi Gandhi also makes in a piece exploring Mercury’s background for NBC. It’s often forgotten that the lead singer was brought up in a Parsi household, and long before he enrolled in London’s Ealing College of Art, Mercury studied piano in a boarding school in Panchgani. His family only moved to England in 1964 after revolution broke out in the wake of Zanzibar’s independence from Britain.

“This is the thing with Freddie Mercury: I think he operated in at least four closets in his life,” Jason King, an associate professor at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Music, who is working on a book about Mercury, tells Gandhi. Those “closets” included his sexuality and the AIDS diagnosis, but also his race and nationality.

Unlike the film’s careful tred of history, the Queen frontman’s layers were visible during his lifetime, but it’s something his fans had to want to look for. For instance, while Mercury did not openly discuss his sexuality during his lifetime, as Adam Lambert, Queen’s latest frontman, recently told the U.K. publication Attitude, “I don’t know how ‘in the closet’ Freddie actually was.” Lambert believes that Mercury navigated the taboos of the time to speak his truth in his own way. “[H]e sort of owned it from the get-go,” says Lambert, who references interviews where Mercury was asked whether he was gay and he’d say: “Yeah as a daffodil… gay as a daffodil.” “I don’t know if they thought he was being flippant, but he never really said, ‘No, I’m not’,” says Lambert.

Writing after Mercury’s death for Paragraph, a journal in modern critical theory, John Lynch, a lecturer in the School of Cultural Studies at Leeds Metropolitan University, characterized Queen’s audience as mostly consisting of “white, straight men seemingly unaware of, or unconcerned by, the gay iconography” that Mercury promoted. “As a star on stage,” he argued, Mercury served as a “‘screen’ onto which any number of fantasies could be projected.” “The very distance between Mercury and the audience acted to keep him apart yet simultaneously permanently available in an imaginary form,” he wrote.

In an interview after his health started to fail him, Mercury hinted at such a discrepency, saying, “When I’m performing, I’m an extrovert, yet inside I’m a completely different man.”