The writer’s dystopia, populated by ‘automaton figures,’ was surprisingly modern

If you’re a fan of the TV series, “Westworld,” you’re probably aware that it’s based on Michael Crichton’s 1973 film of the same name. What you may not know is that the concept has been kicking around for a very long time. While Crichton insists his dystopian vision had no “literary antecedents,” there’s at least one writer who may beg to differ. Charles Dickens imagined a robot theme park way back in 1838. Just like Westworld, the patrons of Dickens’ park are able to enact their “violent delights” on realistic humanoid androids.

In the short story titled, “Full Report of the First Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything,” a group of scientists meet to discuss a variety of proposals, including the classification of a one-eyed horse as “Fitfordogsmeataurious” and a snuffbox-sized machine for more efficient pickpocketing. The most vividly described of these outlandish ideas, though, is entrepreneurial inventor Mr. Coppernose’s suggestion for a park filled with “automaton figures” which would enable wealthy young men to run riot without causing a public nuisance. Sound familiar? So, how do the two parks measure up?

In purely physical terms, Dickens’ park is much smaller. The series’ showrunner, Jonathan Nolan, has indicated that Westworld covers around 500 square miles, while Coppernose suggests a more modest “space of ground of not less than ten miles in length” for his park. But both demonstrate a similar attention to detail when it comes to creating a realistic environment for their patrons to explore. Westworld offers trading outposts, farmsteads and wide open plains populated by robot cowboys, saloon girls and the Ghost Nation Tribe. Coppernose’s park strives to recreate a version of semi-rural England using “highway roads, turnpikes, bridges [and] miniature villages,” inhabited by automaton police officers, cab drivers and elderly women.

Delos Incorporated (the company which owns Westworld) expects its players will use these environments and android “hosts” to engage in both whitehat (heroic) and blackhat (villainous) activities. Meanwhile, Coppernose assumes only the most base and destructive behavior from his park patrons. This is evidenced in various design choices, such as the “gas lamps of real glass, which could be broken at a comparatively small expense per dozen,” and the vocal abilities of the automatons themselves which, when struck, “utter divers groans, mingled with entreaties for mercy, thus rendering the illusion complete and the enjoyment perfect.”

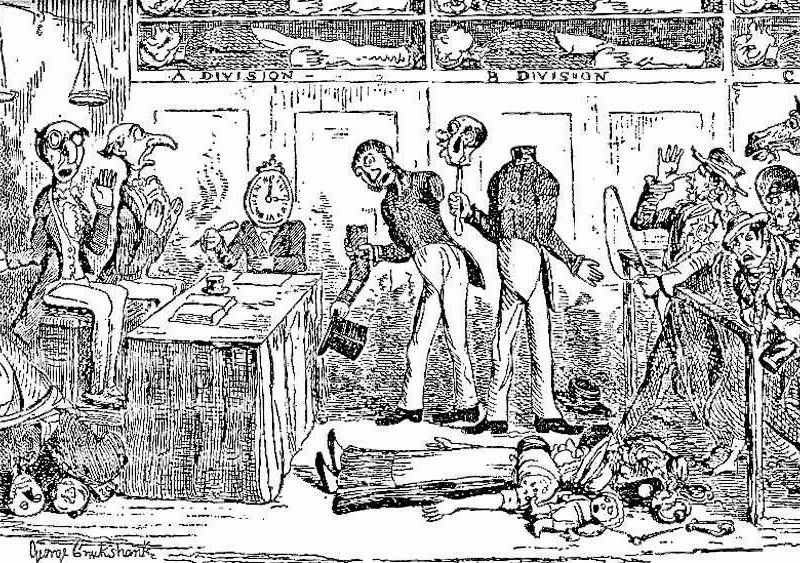

Yet this advanced speech technology isn’t the only thing Coppernose’s automatons have in common with Westworld’s hosts, as demonstrated in George Cruikshank’s illustration. Here the lifelike robots are shown to be operational despite missing limbs – something we’ve seen during diagnostic sessions with Westworld’s damaged hosts in the repair lab.

While Coppernose doesn’t provide specific details of any maintenance crews, it seems he has a similar rotational system in mind when he suggests a stock of 140 automatons, with around half kept in reserve so that broken units can be exchanged. However, rather than the spooky warehouse filled with dormant hosts seen in Westworld, Coppernose has a far more space-saving storage solution, keeping inert robot police officers on shelves until needed.

Only human after all

Although its never been explicitly explained in the show, showrunner Lisa Joy has described the “good samaritan reflex” as a safety measure programmed into all Westworld’s hosts – including the animals. This ensures that if a guest is at risk of endangering themselves or another guest, a host will step in to save them from harm. Humans don’t fare so well in Dickens’ park – Coppernose advocates the use of “live pedestrians … procured from the workhouse” for the wealthy park guests to run down in their cabriolets.

However, this is where a theme only lightly touched on in “Westworld” is brought to the fore in Dickens’ text: the disparity between justice for the rich and the poor. Coppernose’s affluent young adventurers must attend a mock trial following their wild and destructive behavior, where wooden-headed automaton magistrates side with the defendants rather than the robot police attempting to prosecute them. Dickens describes this process as “quite equal to life” serving to underline the inequality at play in the justice system.

While “Westworld” primarily focuses on what it means to be human it does hint at this same idea: that we’re inclined to overlook the bad behavior of the rich and powerful. When wealthy park patron “Man in Black” kills hosts indiscriminately, security chief Ashley Williams says: “That gentleman gets whatever he wants.”

Of course, now that Westworld’s robots have gone rogue, the Man in Black may not go unpunished in season two. Perhaps the retribution Dickens would doubtless have liked to have seen will be delivered not by the courts, but the robots themselves.