An heirloom is charged with both sentiment and purely speculative history

I am related to a man who once knew a man who knew another man who knew George Washington. And to prove it, my family has a souvenir of the great relationship between the first President and that friend of a friend of my now departed relative.

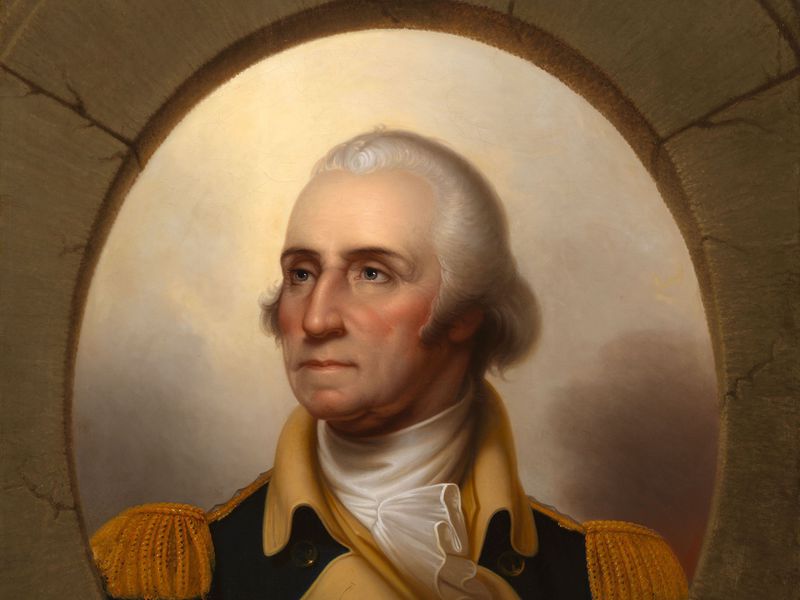

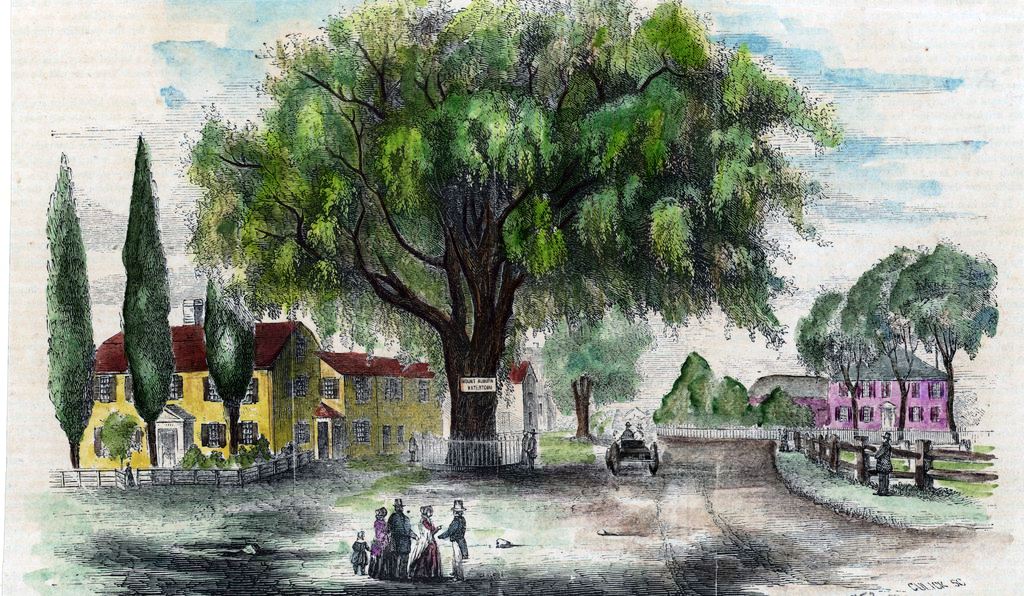

It seems that when Washington was feeling pressed by affairs of state, he would drive out from the then capital city of Philadelphia and visit Belmont, the home of Judge Richard Peters. ”There, sequestered from the world, the torments and cares of business, Washington would enjoy a vivacious, recreative, and wholly unceremonious intercourse with the Judge,” writes historian Henry Simpson in his voluminous The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased.

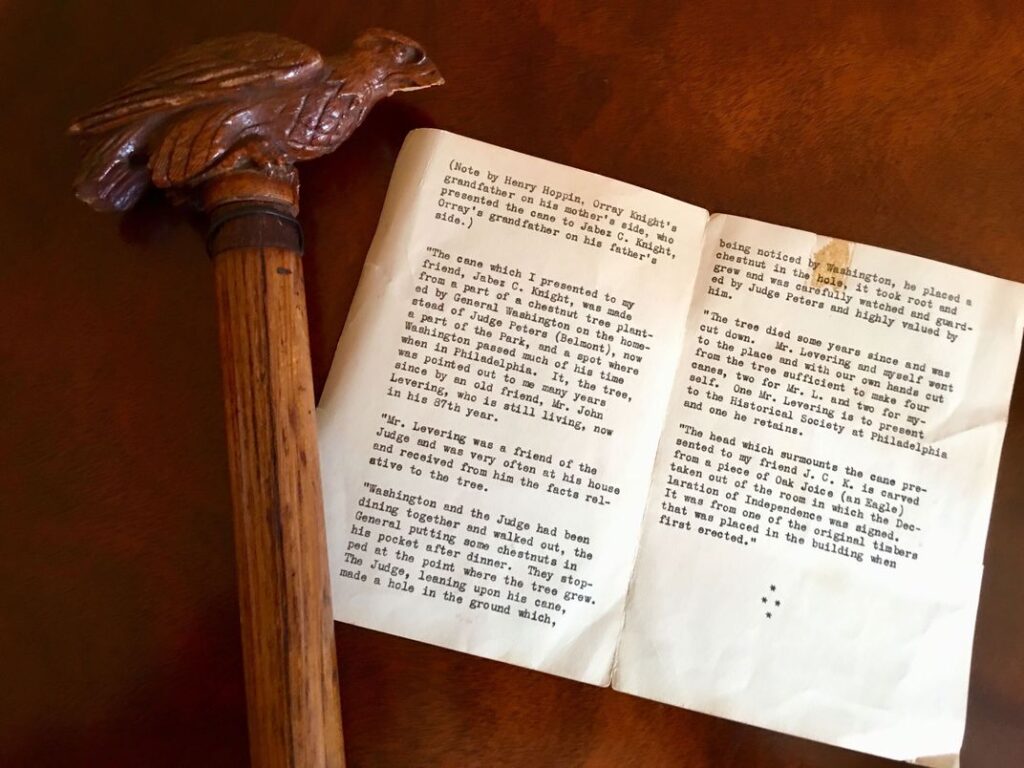

According to Simpson and my 19th-century relative, one Henry Hoppin of Lower Merion, Pennsylvania, Belmont was also home to a grand old chestnut tree planted by Washington himself. Using wood taken from that tree after it died in the 1860s, Hoppin and his friend John Levering carved four walking sticks. In a letter written around 1876, Hoppin, a prudent man, carefully documented the facts relating to his two souvenirs of the President and the tree from which they were carved.

Hoppin’s letter tells the story of the planting of the tree, as told to him by Levering, who was old enough to have known Judge Peters. “Washington and the Judge had been dining together and walked out, the General putting some chestnuts in his pocket after dinner. . . . The Judge, leaning upon his cane, made a hole in the ground which, being noticed by Washington, he placed a chestnut in the hole, it took root and grew and was carefully watched and guarded by Judge Peters and highly valued by him.”

The cane hangs now in my home, inherited from my in-laws (if truth be told, my relationship to Hoppin is rather tenuous). But nonetheless, it was with a certain awe that I first regarded the cane; it was a bond that linked me, however remotely, with the great man.

That feeling remained until I happened on a book called George Washington Slept Here by Karal Ann Marling. Canes and other relics dating back to the time of Washington, it would appear, are fairly common, not to say outright plentiful. Apparently, too, whenever George Washington ate off of, drank from or slept on something, the table, glass or blanket was instantly whisked away by somebody and stored as a memento for future generations.

During the nation’s 1876 Centennial celebration, a mad rush set in to trace or dig up and somehow validate anything that could possibly be linked to Washington. If a grandmother was said to have danced with him, her ball gown was dusted off and treasured because it had once been pressed close to the great general’s stalwart chest. Gloves worn on hands that had reputedly touched President Washington’s were stored away in hope chests. Some Americans treasured bricks from his birthplace at Wakefield, in Virginia, others hoarded wineglasses, cutlery or china that he once dined from. And, oh yes, putative locks of his hair, enough to fill a good-sized barbershop, began turning up everywhere.

To my chagrin, it also seems that the poor man never went anywhere without planting a tree—or just pausing for a moment beneath one. And every time he did so, apparently, a legion of admirers took note and recorded it for posterity. Washington was, of course, a formidable tree planter. His diaries contain some 10,000 words relating to his penchant for planting: “Saturday, 5th. Planted out 20 young Pine trees at the head of my Cherry Walk” or “28th. I planted three french Walnuts in the New Garden and on that side next the work House.” He brought trees in from the forests and had them transplanted on the grounds of Mount Vernon. Not too long ago, a 227-year-old Canadian Hemlock was felled by stiff March winds.

Perhaps it was his admiration for beautiful trees that led him, as legend has it, to stand ceremoniously beneath the branches of a stately elm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on July 3, 1775, the day he took command of his army. The tree that came to be known as the Washington Elm lived until 1923, becoming almost as famous as the President. Its seedlings were transplanted as far west as Seattle. And from one of its huge branches, which blew down sometime before the Philadelphia Centennial Celebration, a man from Milwaukee commissioned the carving of an ornmental chair, as well as quite a number of wooden goblets, urns, vases and, of course, canes.

Washington was and is an American idol revered so deeply and for so long that where he is concerned our collective imaginations have happily blurred fact and fantasy. Maybe old Henry Hoppin was swayed in that way. But then again, maybe not. I’d like to think that on that cold wintry day, Grandpa Hoppin and his old friend John Levering did drive quietly out to Belmont and cut from the historic chestnut tree enough wood to carve a few souvenirs. Perhaps they stood there a moment longer, beneath its sagging branches, to bid the tree farewell before getting into their carriage for the drive home.