Long thought to be primarily women’s work, new analysis of ceramic fragments shows both sexes created pottery at Chaco Canyon.

In the Pueblo communities of New Mexico and Arizona, pottery is a skill that is traditionally passed down from grandmothers and mothers to younger women of the community. This custom was thought to have ancient origins, and archaeologists believed about a thousand years’ worth of ceramics were crafted primarily by women in what is now the southwestern United States. But a new study of pottery at Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico, the center of early Ancestral Pueblo culture 800 to 1,200 years ago, shows men and women were getting their hands dirty at almost equal rates.

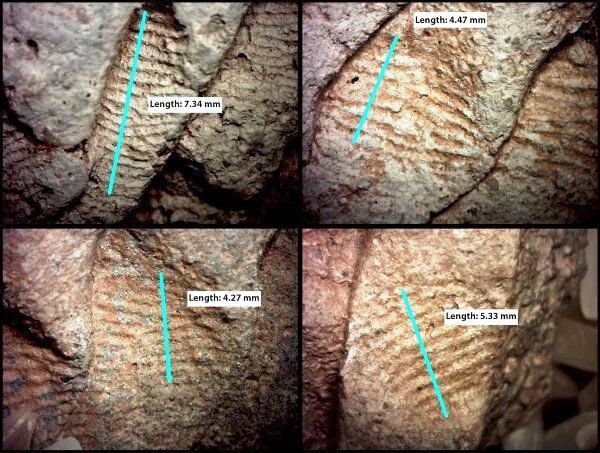

Michelle Z. Donohue at National Geographic reports that the revelation comes from an unusual source: fingerprints left on pottery. The dominant style of pottery at Chaco was corrugated ware, which involves pinching layers of coiled clay together using the thumb and forefinger, leaving ancient fingerprints behind. Several years ago, David McKinney was working at a police station where he was surrounded by fingerprints. He suggested to the his then-advisor John Kantner at the University of North Florida that modern fingerprint forensics might be able to reveal something about the people pinching all those pots together.

Kantner found recent research showing that it is possible to distinguish between male and female fingerprints. The breadth of men’s fingerprint ridges are nine percent wider than those of women. Using this info, Kantner and McKinney examined 985 pieces of broken corrugated ware from Blue J, an archaeological site at Chaco Canyon dating to the 10th and 11th centuries A.D.

According to the new study in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, about 47 percent of the fragments had fingerprints corresponding to males and 40 percent came from women or juveniles. Another 12 percent were not conclusive. What’s more, the percentages had changed over time. Among the oldest pottery fragments, male fingerprints appeared on 66 percent. However, by the end of the time period represented, men and women made pots about equally.

“This certainly challenges the notion that one gender was involved in pottery and one was clearly not,” Kantner tells Donahue. “Perhaps we can begin to wonder if that’s also true for other activities that took place in this community at this time, and challenge the idea that gender is one of the first things to become divided in the labor of a community.”

According to a press release, the gender shifts in pottery making happened during a period when Chaco was becoming an important regional political and religious center. Increased demands for ceramic goods may have caused traditional gender roles to shift. “The results challenge previous assumptions about gendered divisions of labor in ancient societies and suggest a complex approach to gender roles throughout time,” Kantner says.

Ceramics expert Barbara Mills from the University of Arizona tells Donahue that the findings agree with what researchers know about specialization. Men tend to move into activities like making pots when the product is in demand, and often their whole family will become involved in the production.

It’s not clear what factors drove more men to start pinching clay pots around Chaco, but Kantner says large amounts of goods were flowing into Chaco Canyon during this period. It’s possible increased demand at Chaco led to more men working in pottery in surrounding communities to supply all the corrugated ware needed to provide tribute to the site.

Kantner says in the release that understanding the gender of people who made the pots has something to say about ancient socities beyond Chaco as well. “An understanding of the division of labor in different societies, and especially how it evolved in the human species, is fundamental to most analyses of social, political and economic systems,” he says.

In many cases, those divisions of labor aren’t immediately apparent and have to be teased out of the archaeological record. Just last month, a study of the worn teeth of a woman in Egypt revealed that she was likely involved in the production of papyrus goods, like baskets and mats, something not previously recorded. The written record of Egypt presents women performing certain specialized roles, such as priestess, mourner, midwife and weaver, but it doesn’t represent the economic contributions of average women. Earlier this year, another study found blue pigment in the teeth of a medieval nun, indicating that she illuminated manuscripts, a profession previously believed to be the domain of male monks.

By reexamining the artifacts left behind by ancient cultures, we can begin to understand the complex ways women and men contributed to the societies of the past.