Though the practice is now more associated with Halloween, spooking out your family is well within the Christmas spirit

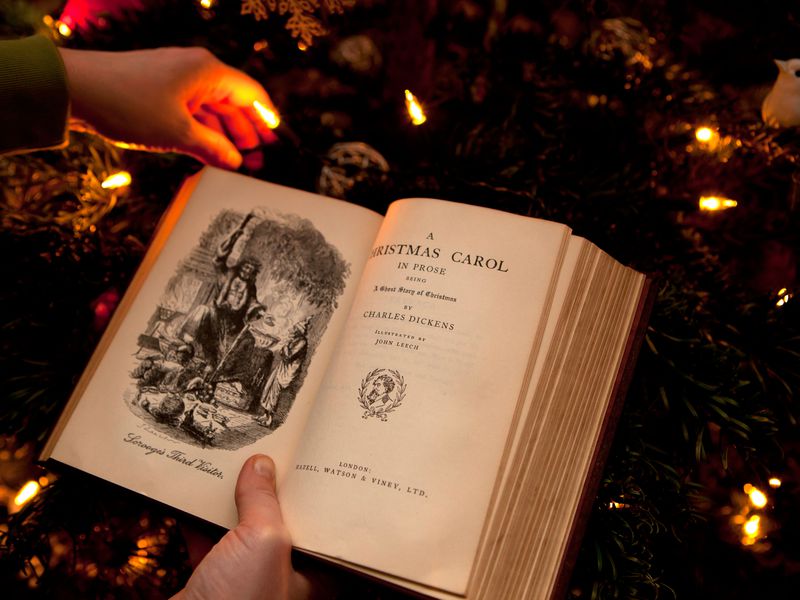

For the last hundred years, Americans have kept ghosts in their place, letting them out only in October, in the run-up to our only real haunted holiday, Halloween. But it wasn’t always this way, and it’s no coincidence that the most famous ghost story is a Christmas story—or, put another way, that the most famous Christmas story is a ghost story. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was first published in 1843, and its story about a man tormented by a series of ghosts the night before Christmas belonged to a once-rich, now mostly forgotten tradition of telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve. Dickens’ supernatural yuletide terror was no outlier, since for much of the 19th century, was the holiday indisputably associated with ghosts and the specters.

“Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories,” humorist Jerome K. Jerome wrote in his 1891 collection, Told After Supper. “Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres. It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood.”

Telling ghost stories during winter is a hallowed tradition, a folk custom stretches back centuries, when families would wile away the winter nights with tales of spooks and monsters. “A sad tale’s best for winter,” Mamillius proclaims in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale: “I have one. Of sprites and goblins.” And the titular Jew of Malta in Christopher Marlowe’s play at one point muses, “Now I remember those old women’s words, Who in my wealth would tell me winter’s tales, And speak of spirits and ghosts by night.”

Based in folklore and the supernatural, it was a tradition the Puritans frowned on, so it never gained much traction in America. Washington Irving helped resurrect a number of forgotten Christmas traditions in the early 19th century, but it really was Dickens who popularized the notion of telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve. The Christmas issues of the magazines he edited, Household Words and (after 1859) All the Year Round, regularly included ghost stories—not just A Christmas Carol but also works like The Chimes and The Haunted Man, both of which also feature an unhappy man who changes his ways after visitation by a ghost. Dickens’ publications, which were not just winter-themed but explicitly linked to Christmas, helped forge a bond between the holiday and ghost stories; Christmas Eve, he would claim in “The Seven Poor Travellers” (1854), is the “witching time for Story-telling.”

Dickens discontinued the Christmas publications in 1868, complaining to his friend Charles Fechter that he felt “as if I had murdered a Christmas number years ago (perhaps I did!) and its ghost perpetually haunted me.” But by then the ghost of Christmas ghost stories had taken on an afterlife of its own, and other writers rushed to fill the void that Dickens had left. By the time of Jerome’s 1891 Told After Supper, he could casually joke about a tradition long ensconced in Victorian culture.

If some of these later ghost stories haven’t entered the Christmas canon as Dickens’ work did, there’s perhaps a reason. As William Dean Howells would lament in a Harper’s editorial in 1886, the Christmas ghost tradition suffered from the gradual loss of Dickens’ sentimental morality: “the ethical intention which gave dignity to Dickens’ Christmas stories of still earlier date has almost wholly disappeared.”

While readers could suspend their disbelief for the supernatural, believing that such terrors could turn a man like Scrooge good overnight was a harder sell. “People always knew that character is not changed by a dream in a series of tableaux; that a ghost cannot do much towards reforming an inordinately selfish person; that a life cannot be turned white, like a head of hair, in a single night, but the most allegorical apparition; …. and gradually they ceased to make believe that there was virtue in these devices and appliances.”

Dickens’ genius was to wed the gothic with the sentimental, using stories of ghosts and goblins to reaffirm basic bourgeois values; as the tradition evolved, however, other writers were less wedded to this social vision, preferring the simply scary. In Henry James’s famous gothic novella, The Turn of the Screw, the frame story involves a group of men sitting around the fire telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve—setting off a story of pure terror, without any pretension to charity or sentimentality.

At the same time that the tradition of Christmas ghosts had begun to ossify, losing the initial spiritual charge that drove its popularity, a new tradition was being imported from across the Atlantic, carried by the huge wave of Scottish and Irish immigrants coming to America: Halloween.

The holiday as we now know it is an odd hybrid of Celtic and Catholic traditions. It borrows heavily from the ancient pagan holiday Samhain, which celebrates the end of the harvest season and the onset of winter. As with numerous other pagan holidays, Samhain was in time merged with the Catholic festival of All Souls’ Day, which could also be tinged towards obsessions with the dead, into Halloween—a time when the dead were revered, the boundaries between this life and the afterlife were thinnest, and when ghosts and goblins ruled the night.

Carried by Scottish and Irish immigrants to America, Halloween did not immediately displace Christmas as the preeminent holiday for ghosts—partly because for several decades it was a holiday for Scots. Scottish immigrants (and to a lesser extent Irish immigrants as well) tried to dissociate Halloween from its ghostly implications, trying unsuccessfully to make it about Scottish heritage, as Nicholas Rogers notes in his Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night: “There were efforts, in fact, to recast Halloween as a day of decorous ethnic celebration.” Organizations such as the Caledonian Society in Canada observed Halloween with Scottish dances and music and the poetry of Robbie Burns, while in New York the Gaelic Society commemorated Halloween with a seannches: an evening of Irish poetry and music.

Americans’ hunger for ghosts and nightmares, however, outweighed their hunger for Irish and Scottish culture, and Americans seized on Halloween’s supernatural, rather than cultural, aspects—we all know now how this turned out.

The transition from Christmas to Halloween as the preeminent holiday for ghosts was an uneven one. Even as late as 1915, Christmas annuals of magazines were still dominated by ghost stories, and Florence Kingsland’s 1904 Book of Indoor and Outdoor Games still lists ghost stories as fine fare for a Christmas celebration: “The realm of spirits was always thought to be nearer to that of mortals on Christmas than at any other time,” she writes.

For decades, these two celebrations of the oncoming winter bookended a time when ghosts were in the air, and we kept the dead close to us. My own family has for years invited friends over around the holidays to tell ghost stories. Instead of exchanging gifts, we exchange stories—true or invented, it doesn’t matter. People are inevitably sheepish at first, but once the stories start flowing, it isn’t long before everyone has something to offer. It’s a refreshing alternative to the oft-forced yuletide joy and commercialization; resurrecting the dead tradition of ghost stories as another way to celebrate Christmas.

In his Harper’s editorial, Howells laments the loss of the Dickensian ghost story, waxing nostalgic for a return to scary stories with a firm set of morals:

“It was well once a year, if not oftener, to remind men by parable of the old, simple truths; to teach them that forgiveness, and charity, and the endeavor for life better and purer than each has lived, are the principles upon which alone the world holds together and gets forward. It was well for the comfortable and the refined to be put in mind of the savagery and suffering all round them, and to be taught, as Dickens was always teaching, that certain feelings which grace human nature, as tenderness for the sick and helpless, self-sacrifice and generosity, self-respect and manliness and womanliness, are the common heritage of the race, the direct gift of Heaven, shared equally by the rich and poor.”

As the nights darken and we head towards the new year, filled with anxiety and hope, what better emissaries are there to bring such a message than the dead?