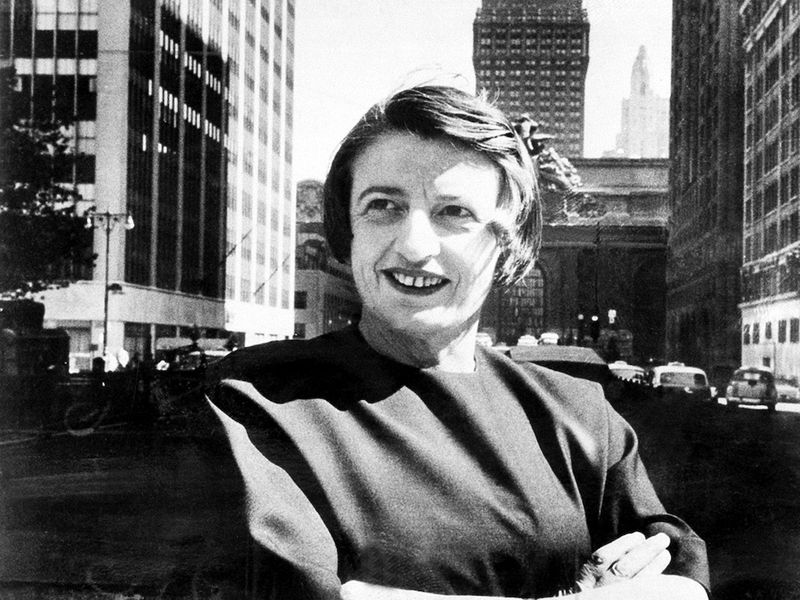

Seventy-five years after the publishing of ‘The Fountainhead’, a look back at the public intellectuals who disseminated her Objectivist philosophy

For 19-year-old Nathan Blumenthal, reading Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead for the first time was nothing short of an epiphany. Published several years earlier, in 1943, Blumenthal wrote of finding the book in his memoir, My Years with Ayn Rand. “There are extraordinary experiences in life that remain permanently engraved in memory. Moments, hours, or days after which nothing is ever the same again. Reading this book was such an experience.”

Little could the Canadian teen have imagined that within the next 10 years he would, with Rand’s approval, change his name to Nathaniel Branden; become one of Rand’s most important confidantes—as well as her lover; and lead a group of thinkers on a mission to spread the philosophy of Objectivism far and wide.

At 19, Branden was only a teenager obsessed by the words of this Russian-born writer—until March 1950, when Rand responded to the letter he’d sent and invited him to visit her. That meeting was the start of a partnership that would last for nearly two decades, and the catalyst for the creation a group she dubbed “The Class of ’43,” for the year The Fountainhead was published. Later, they knowingly gave themselves the ironic name “The Collective.” And although 75 years have passed since The Fountainhead was first published, the impact of that book—and the people who gathered around Rand because of it—still play an important role in American political thinking.

Leading Republicans today, including Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, have spoken publicly of her influence. In 2005, he told members of the Rand-loving Atlas Group that the author’s books were “the reason I got involved in public service, by and large.” Mick Mulvaney, a founding member of the House Freedom Caucus and current director of the Office of Management and Budget, spoke in 2011 of his fondness for Rand’s Atlas Shrugged: “It’s almost frightening how accurate a prediction of the future the book was,” he told NPR. Other self-described Rand acolytes who have served in the Trump Administration include former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (“Favorite Book: Atlas Shrugged”) and current Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (Atlas Shrugged “really had an impact on me”).

Initially, Branden was responsible for bringing new members into the “Class of ‘43” and mostly recruited family and friends who were equally riveted by The Fountainhead so that they could listen to Rand’s philosophy. Without him, the group may never have formed; as Rand herself said, “I’ve always seen [the Collective] as a kind of comet, with Nathan as the star and the rest as his tail.” Branden brought his soon-to-be-wife, Barbara, as well as siblings and cousins. Soon the core group included psychiatrist Allan Blumenthal, philosopher Leonard Peikoff, art historian Mary Ann Sures and economist Alan Greenspan. Every Saturday evening, during the years in which Rand was engaged writing Atlas Shrugged, the Collective gathered in Rand’s apartment and listened to her expound on the Objectivist philosophy or read the newest pages of her manuscript.

“Even more than her fiction or the chance to befriend a famous author, Rand’s philosophy bound the Collective to her. She struck them all as a genius without compare,” writes historian Jennifer Burns in Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. As for Rand, she “saw nothing unusual in the desire of her students to spend each Saturday night with her, despite being more than twenty years her junior. The collective put Rand in the position of authority she had always craved.”

Rand’s fiction and her philosophy butted up against conservatism of the era (which saw inherent value in the federal government even as it opposed social programs like the New Deal) and then split from it entirely. She was less interested in reshaping her adoptive country’s democratic government than in upending it completely. While politicians of the 1950s were rocked by McCarthyism and a new concern for traditional values and the nuclear family, Rand took it upon herself to forge a new path into libertarianism—a system being developed by various economists of the period that argued against any government influence at all.

According to Rand’s philosophy, as espoused by the characters in her novels, the most ethical purpose for any human is the pursuit of happiness for one’s self. The only social system in which this morality can survive is completely unfettered capitalism, where to be selfish is to be good. Rand believed this so fervently that she extended the philosophy to all aspects of life, instructing her followers on job decisions (including advising Greenspan to become an economic consultant), the proper taste in art (abstract art is “an enormous fraud”), and how they should behave.

Branden built upon Rand’s ideas with his own pop psychology, which he termed “social metaphysics.” The basic principle was that concern over the thoughts and opinions of others was pathological. Or, as Rand more bluntly phrased it while extolling the benefits of competence and selfishness, “I don’t give a damn about kindness, charity, or any of the other so-called virtues.”

These concepts were debated from sunset to sunrise every Saturday at Rand’s apartment, where she lived with her husband, Frank O’Connor. While Rand kept herself going through the use of amphetamines, her followers seemed invigorated merely by her presence. “The Rand circle’s beginnings are reminiscent of Rajneesh’s—informal, exciting, enthusiastic, and a bit chaotic,” writes journalist Jeff Walker in The Ayn Rand Cult.

But if the Saturday salons were exciting, they could also be alienating for outsiders. Economist Murray Rothbard, also responsible for contributing to the ideals of libertarianism, brought several of his students to meet Rand in 1954 and watched in horror as they submitted to vitriol from Rand whenever they said anything that displeased her. The members of the Collective seemed “almost lifeless, devoid of enthusiasm or spark, and almost completely dependent on Ayn for intellectual sustenance,” Rothbard later said. “Their whole manner bears out my thesis that the adoption of her total system is a soul-shattering calamity.”

Branden only fanned the flames by requiring members to subject themselves to psychotherapy sessions with him, despite his lack of training, and took it upon himself to punish anyone who espoused opinions that varied with Rand’s by humiliating them in front of the group. “To disparage feelings was a favorite activity of virtually everyone in our circle, as if that were a means of establishing one’s rationality,” Branden said.

According to journalist Gary Weiss, the author of Ayn Rand Nation: The Hidden Struggle for America’s Soul, all of these elements made the Collective a cult. “It had an unquestioned leader, it demanded absolute loyalty, it intruded into the personal lives of its members, it had its own rote expressions and catchphrases, it expelled transgressors for deviation from accepted norms, and expellees were ‘fair game’ for vicious personal attacks,” Weiss writes.

But Branden wasn’t satisfied with simply parroting Rand’s beliefs to those who were already converted; he wanted to share the message even more clearly than Rand did with her fiction. In 1958, a year after Atlas Shrugged was published (it was a best-seller, but failed to earn Rand the critical acclaim she craved), Branden started the Nathaniel Branden Lectures. In them, he discussed principles of Objectivism and the morality of selfishness. Within three years, he incorporated the lecture series as the Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI), and by 1964 the taped lectures played regularly in 54 cities across Canada and the United States.

“Rand became a genuine public phenomenon, particularly on college campuses, where in the 1960s she was as much a part of the cultural landscape as Tolkien, Salinger, or Vonnegut,” writes Brian Doherty in Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement. “NBI’s lectures and advice on all aspects of life, as befits the totalistic nature of Objectivism, added to the cult-like atmosphere.”

Meanwhile, as her books sold hundreds of thousands of copies, Rand continued amassing disciples. Fan mail continued to pour in as new readers discovered The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, and these letters were sometimes a useful recruiting tool. Writers who seemed particularly well-informed were given assignments to prove themselves before being invited to the group, writes Anne C. Heller in Ayn Rand and the World She Made. “In this way, a Junior Collective grew up.”

The Collective continued as an ever-expanding but tight-knit group until 1968. It was then that Branden, who had already divorced his wife, chose to reveal he was having an affair with a younger woman. Rand responded by excoriating him, his ex-wife Barbara, and the work that Branden had done to expand the reach of Objectivism. While members of the group like Greenspan and Peikoff remained loyal, the Collective was essentially disbanded; the Randians were left to follow their own paths.

Despite the dissolution of the group, Rand had left an indelible mark on her followers and the culture at-large. Greenspan would go on to serve as Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006, while Branden continued working at his institute, though with a slightly tempered message about Objectivism and without any relationship with Rand. In 1998, Modern Library compiled a readers’ list of the 20th century’s greatest 100 books that placed Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead in the first and second spots, respectively; both continue to sell hundreds of thousands of copies.

The irony of her free-thinking followers naming themselves “The Collective” seems similar to the techniques she used in her writing, often reminiscent of Soviet propaganda, says literary critic Gene H. Bell-Villada. “In a perverse way, Rand’s orthodoxies and the Randian personality cult present a mirror image of Soviet dogmas and practices,” Bell-Villada writes. “Her hard-line opposition to all state intervention in the economy is a stance as absolute and unforgiving as was the Stalinist program of government planning and control.”