Army medic Ray Lambert, now 98, landed with the first assault wave on Omaha Beach. Seventy-five years later, he could be the last man standing

As world leaders and assorted dignitaries join the throngs of grateful citizens and remembrance tourists in Normandy this year to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day, one group in particular will command a special reverence: veterans of the actual battle.

Their numbers are rapidly dwindling. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that fewer than 3 percent of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II are still living. For those who saw the fiercest combat, the numbers are even more sobering. One telling measure: As of mid-May, just three of the war’s 472 Medal of Honor winners were still alive. The youngest D-Day vets are now in their mid-90s, and it is generally understood, if not necessarily said aloud, that this year’s major anniversary salutes may be the final ones for those few surviving warriors.

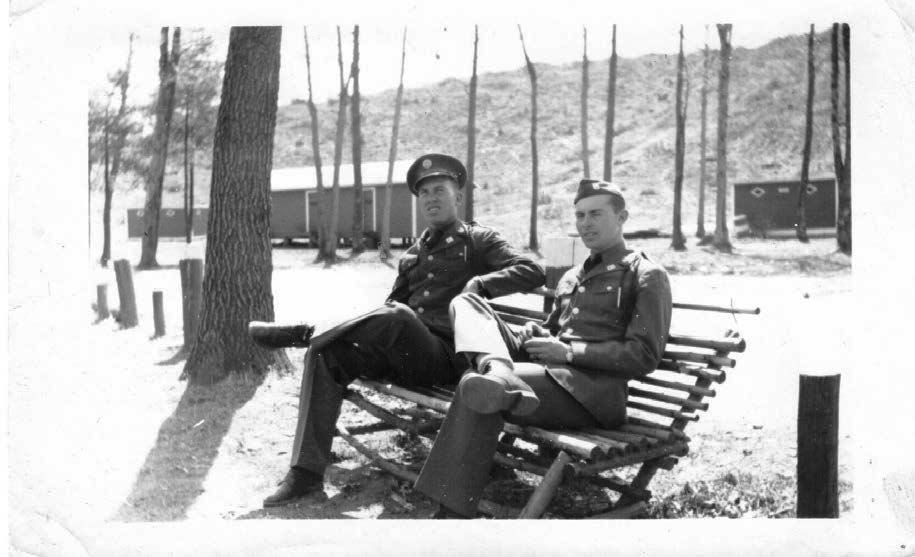

One of the returning American vets is 98-year-old Arnold Raymond “Ray” Lambert, who served as a medic in the 16th Infantry Regiment of the army’s storied First Division, the “Big Red One.”

Lambert, then 23, was but one soldier in the largest combined amphibious and airborne invasion in history, a mighty armada of some 160,000 men, 5000 vessels and 11,000 aircraft—the vanguard of the Allied liberation of Western Europe from what Churchill had called “a monstrous tyranny never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime.”

When D-Day finally arrived, after years of planning and mobilization, the Big Red One was at the point of the spear.

In the early dawn of June 6, 1944, Lambert’s medical unit landed with the first assault wave at Omaha Beach, where Wehrmacht troops were especially well-armed, well-fortified and well-prepared. Drenched, weary and seasick from the nighttime Channel crossing in rough seas, the GIs faced daunting odds. Pre-dawn aerial bombardments had landed uselessly far from their targets; naval gunfire support had ended; amphibious tanks were sinking before they reached land. Many of the landing craft were swamped by high waves, drowning most of their men. Soldiers charged forward in chest-deep waters, weighed down by as much as 90 pounds of ammunition and equipment. As they came ashore, they faced withering machine gun, artillery and mortar fire.

In the opening minutes of battle, by one estimate, 90 percent of the frontline GIs in some companies were killed or wounded. Within hours, casualties mounted into the thousands. Lambert was wounded twice that morning but was able to save well more than a dozen lives thanks to his bravery, skill and presence of mind. Impelled by instinct, training and a profound sense of responsibility for his men, he rescued many from drowning, bandaged many others, shielded wounded men behind the nearest steel barrier or lifeless body, and administered morphine shots—including one for himself to mask the pain of his own wounds. Lambert’s heroics only ended when a landing craft ramp weighing hundreds of pounds crashed down on him as he attempted to help a wounded soldier emerge from the surf. Unconscious, his back broken, Lambert was tended to by medics and soon found himself on a vessel heading back to England. But his ordeal was far from over. “When I came out of the army I weighed 130 pounds,” Lambert says. “I’d been in hospital for almost a year after D-Day, in England, then back in the States, before I was able to walk and really get around too good.”

The now-annual D-Day commemorations initially dispensed with pomp and circumstance. On June 6, 1945, just a month after V-E Day, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower simply granted troops a holiday, declaring that “formal ceremonies would be avoided.” In 1964, Ike revisited Omaha Beach with Walter Cronkite in a memorable CBS News special. Twenty years later, President Ronald Reagan delivered a soaring address at Pointe du Hoc, overlooking the beach. He praised the heroism of the victorious allied forces, spoke of reconciliation with Germany and the Axis powers, which had also suffered greatly, and reminded the world: “The United States did its part, creating the Marshall Plan to help rebuild our allies and our former enemies. The Marshall Plan led to the Atlantic alliance—a great alliance that serves to this day as our shield for freedom, for prosperity, and for peace.”

Ray Lambert has visited Normandy many times and is returning for the 75th anniversary to take part in solemn ceremonies, visit the war museums, and pay his respects to the 9,380 men buried in the American military cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, on the high bluff overlooking the hallowed beach. Lambert knew many of those men from D-Day and earlier amphibious assaults and pitched battles in North Africa and Sicily, where he earned a Silver Star, Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts. After D-Day, he was awarded another Bronze Star and Purple Heart. There is evidence that he earned two more Silver Stars—one each in Normandy and Sicily—but official paperwork has been lost or destroyed, and Lambert is not the sort of man to claim honors that might not be absolutely clear.

The tranquil seaside scene of today’s Normandy coastline is very different from the one etched in Lambert’s soul. “Where tourists and vacationers see pleasant waves, I see the faces of drowning men,” Lambert writes in Every Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day, the First Wave at Omaha Beach and a World at War, co-authored with writer Jim DeFelice and published on May 28. “Amid the sounds of children playing, I hear the cries of men pierced by Nazi bullets.”

He especially remembers the sound of combat, a furious cacophony unlike anything in civilian life. “The noise of war does more than deafen you,” he writes. “It’s worse than shock, more physical than something thumping against your chest. It pounds your bones, rumbling through your organs, counter-beating your heart. Your skull vibrates. You feel the noise as if it’s inside you, a demonic parasite pushing at every inch of skin to get out.”

Lambert brought home those memories, which still rear up some nights. Yet he somehow survived the slaughter and came home to raise a family, thrive as a businessman and inventor, and contribute to the life of his community. Ray lives with his wife Barbara in a quiet lakeside home near Southern Pines, North Carolina, where they recently celebrated their 36th anniversary. His first wife, Estelle, died of cancer in 1981; they were married for 40 years. He enjoys meeting friends for 6 a.m. coffee at the village McDonalds’s and says he keeps in touch with 1st Infantry Division folks at Fort Riley, Kansas. In 1995, he was named a Distinguished Member of the 16th Infantry Regiment Association. In that role, he tells his story to schoolchildren, Lions Clubs, and other organizations.

Is Lambert the last man standing? Maybe not, but he’s certainly close.

“I have been trying for months and months track down guys who had been in the first wave,” says DeFelice, whose books include the bestselling American Sniper, a biography of General Omar Bradley, and a history of the Pony Express. He has spoken with Charles Shay, 94, a medic who served under Ray that morning who will also participate in this week’s Normandy ceremonies, and has learned of just one other veteran of the initial landing at Omaha Beach, a man in Florida who is not in good health. “Ray is definitely one of the last survivors of the first wave,” DeFelice says.

Longevity is in Lambert’s genes. “My father lived to be 101, my mother lived to be 98,” he says. “I have two children, four grandchildren and I think I’ve got nine great-grandchildren now,” he says. “For breakfast I like some good hot biscuits with honey and butter, or I like some fried country ham and a biscuit. The kids say, ‘Oh, Poppy, that’s not good for you.’ And I tell ’em, well I’ve been eating that all my life, and I’m 98 years old!”

Lambert says he learned to look out for himself growing up in rural Alabama during the Great Depression, an experience he believes toughened him for later challenges. “We were always looking for work to help out the family, because there was no money to speak of,” he says.

As a schoolboy, he cut logs for a dollar a day with a two-man, crosscut saw, right beside the grown men. He helped out on his uncle’s farm, tending to horses and cows, fetching firewood for the stove, learning to patch up balky farm machinery. “In those days,” he says, “we didn’t have running water or electricity. We had outhouses and we used oil lamps. I had to take my turn at milking the cows, churning the milk for butter and drawing well water with a rope and bucket. Sometimes we would have to carry that water for 100 to 150 yards back to the house. That was our drinking water and water for washing up.”

At 16, he found work with the county veterinarian, inoculating dogs for rabies as required by law. He wore a badge and carried a gun. “I’d drive out to a farm—I didn’t have a license, but no one seemed too concerned in those days—and some of these farmers didn’t like the idea of you coming out and bothering them,” he says. “Many times I’d drive up and ask if they had any dogs. They would say no. Then all of a sudden the dog would come running out from under the house barking.”

In 1941, months before Pearl Harbor, Lambert decided to enlist in the army. He told the recruiter he wanted to join a fighting unit and was placed in the 1st Division and assigned to the infantry’s medical corps, a nod to his veterinary skills. “Which I thought that was kind of funny,” he says. “If I could take care of dogs, I could take care of dogfaces—that’s what they called ’em.”

DeFelice says it took months to persuade Lambert to do the book. Like many combat veterans, he is reluctant to call attention to himself or seek glory when so many others paid a heavier price. Some things are hard to relive, hard to return from. “We’re taught in our life, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’” Lambert says. “When you go into the military that all changes.”

For him, the shift occurred during the North Africa campaign, when at first the Americans were being pushed around by hardened German troops led by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. The U.S. commander, General Terry Allen, told his troops they had to learn how to kill. “And it wasn’t but a few days until you saw your buddies getting killed and mangled and blown away before you realize you either kill or be killed,” Lambert says. “And then when you get back home, you’re faced with another change, a change back to the way you were, to be kind and all this kind of stuff. Many men can’t handle that very well.”

Ultimately, he agreed to collaborate with DeFelice and write Every Man a Hero because of the army buddies he left behind, comrades who live on in memory and spirit.

“I got to thinking very seriously about the fact that many of my men were killed,” he says. “Sometimes I was standing right by one of my guys, and a bullet would get him, and he’d drop dead against me. So I’m thinking about all my buddies that couldn’t tell their stories, that would never know if they had children, would never know those children or grow up to have a home and a loving family.”

The responsibility he felt for those men on Omaha Beach 75 years ago has never left Ray Lambert, and it never will.