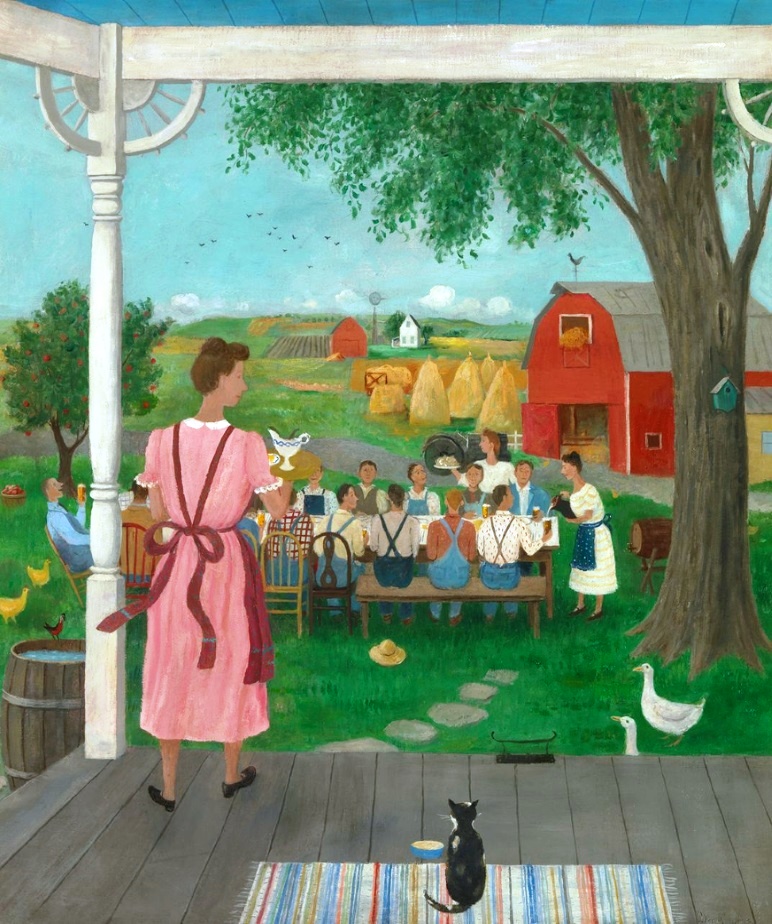

It would be easy to mistake the painting Harvest Time for an uncomplicated image of Midwestern bliss, a picture of ease and plenty after a hard day’s work. It is an unassuming portrayal of a picnic in rural Kansas, with a group of farm workers gathered congenially around a table, drinking beer and laughing. The sun is shining, the hay is piled high and friendly barnyard animals roam over lush green grass. In fact, Harvest Time was created with a specific goal: to convince American women to buy beer.

It was 1945 and the United States Brewers Foundation, an advocacy group for the beer industry, sought out the artist, Doris Lee, to paint something for an advertising campaign they called “Beer Belongs.” The ads, which ran in popular women’s magazines like McCall’s and Collier’s featured works of art that equated beer drinking with scenes of wholesome American life. The artworks positioned beer as a natural beverage to serve and to drink in the home.

“Lee was one of the most prominent American women artists in the 1930s and the 1940s,” says Virginia Mecklenburg, chief curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where Lee’s Harvest Time can be seen on the museum’s first floor. The artwork is featured in the next episode of “Re:Frame,” a new video web series, that explores art and the history of art via the lens of the vast expertise housed at the Smithsonian Institution.

Born in 1905 in Aledo, Illinois, Lee was celebrated for her images of small-town life. She was known for portraying the simple pleasures of rural America—family gatherings, holiday meals, the goings-on of the country store—with thoughtful and sincere detail. She “painted what she knew, and what she knew was the American Midwest, the Great Plains states, the farmlands near where she had grown up,” says Mecklenburg.

For American women, negative perceptions of beer began as early as the mid-1800’s. “Really, from the mid-19th-century, into the 20th-century, beer came to be associated with the working man, who was drinking outside of the home at a saloon or a tavern, and that was a problematic factor of the identity of beer that helped lead to Prohibition,” says Theresa McCulla, the Smithsonian’s beer historian, who is documenting the industry as part of the American Brewing History Initiative for the National Museum of American History.

Prohibition, the 13-year period when the United States banned the production, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages, cemented the perception among women that beer was an immoral drink. “When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, brewers had a bit of a challenge ahead of them,” says McCulla. “They felt like they really needed to rehabilitate their image to the American public. They almost needed to reintroduce themselves to American consumers.”

“In the 1930’s, going into… the war era leading up to 1945, you see a concentrated campaign among brewers to create this image of beer as healthful and an intrinsic component of the American diet, something that was essential to the family table,” she says.

The Brewers Foundation wanted to reposition beer as a central part of American home life. According to the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, who created the “Beer Belongs” campaign: “The home is the ultimate proving ground for any product. Once accepted in the home, it becomes part of established ways of living.” And in the mid-1940s, American home life was squarely the realm of women. The smart incorporation of fine art into the campaign added a level of distinction and civility. Viewers were even invited to write to the United States Brewers Foundation for reprints of the artworks “suitable for framing,” subtly declaring the advertisements—and beer by association–appropriate for the home.

“Women were important, intrinsic to the brewing industry, but really for managing the purse strings,” says McCulla, “women were present as shoppers, and also very clearly as the figures in the household who served beer to men.”

Doris Lee imbued her work with a sense of nostalgia, an emotion that appealed to the United States Brewers Foundation when they conceived of the “Beer Belongs” campaign. “Even though many Americans at this time were moving from rural into urban areas, brewers often drew on scenes of rural life, as this kind of authentic, wholesome root of American culture, of which beer was a crucial part,” says McCulla.

As a woman, Doris Lee’s participation legitimated the campaign. The advertisement blithely pronounced: “In this America of tolerance and good humor, of neighborliness and pleasant living, perhaps no beverage more fittingly belongs than wholesome beer, and the right to enjoy this beverage of moderation, this too, is part of our own American heritage or personal freedom.”

Though women weren’t considered the primary drinkers, their perception of beer was the driving force in making it socially acceptable in the wake of Prohibition. Using artworks like Harvest Time the “Beer Belongs” campaign cleverly equated beer drinking with American home life, breaking down the stigma previously associated with the brew.

The United States Brewers Foundation succeeded in changing American perceptions of beer. Today, beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in the United States, with per capita consumption measured in 2010 at 20.8 gallons a year.