They delivered stranded performers to the 1969 music festival, and carried sick hippies out.

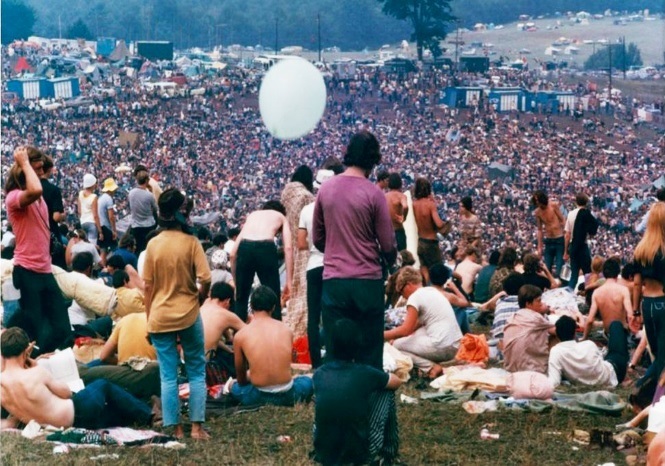

On August 15, 1969, the traffic heading to Bethel, New York, was bumper to bumper. More than 400,000 people were headed to the 3-day-long Woodstock Music & Art Fair in the Catskill mountains, and the five narrow roads leading to the festival site were quickly overwhelmed. People simply abandoned their cars and began to walk. Police would later estimate that the roads were backed up for more than 20 miles.

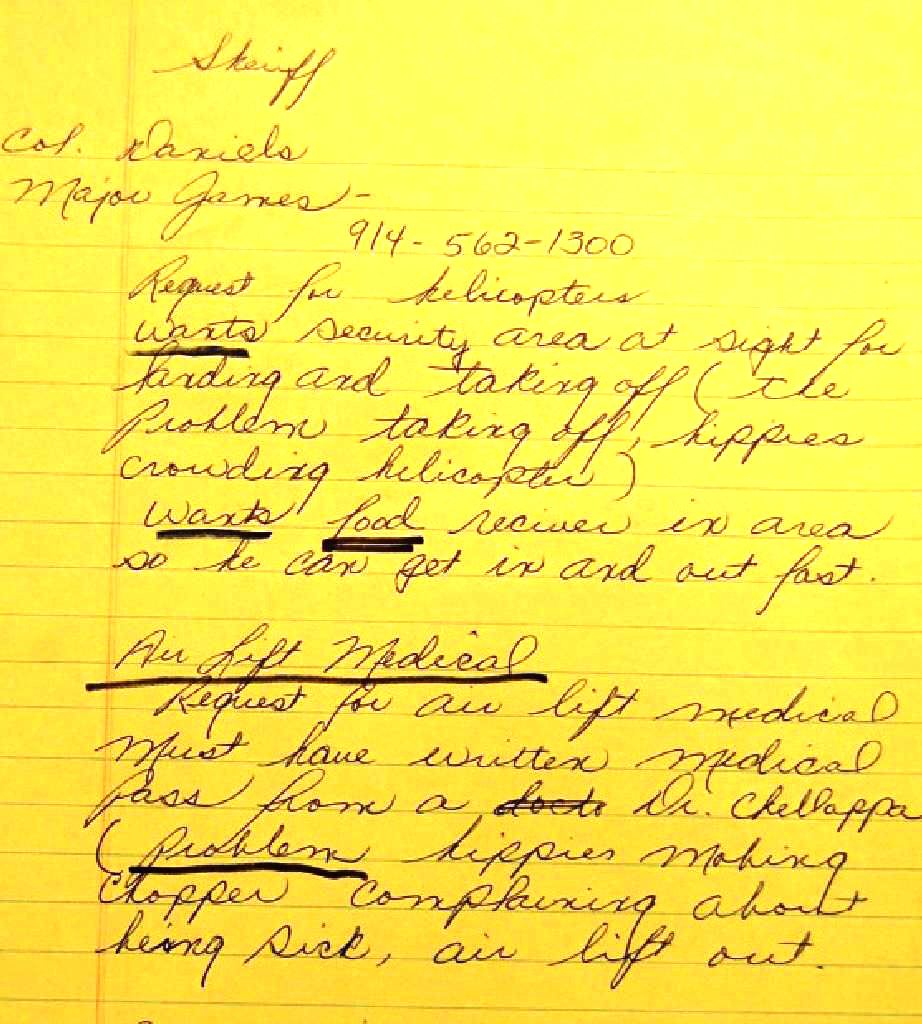

It wasn’t just festivalgoers who were caught in the sprawling traffic; the musicians were stuck as well. But the concert producers quickly came up with a contingency plan: helicopters. “There wouldn’t have been a Woodstock if it weren’t for the Army,” folk singer Richie Havens would tell the (Florida) Sun-Sentinel in 1993. “The Army Reserves actually brought the acts to and from the stage.” Aircraft crews—military and private—would go on to do much more; they also brought food and medical personnel to the site, and airlifted sick or injured festivalgoers to nearby hospitals.

Havens wasn’t meant to be Woodstock’s opening act; he was supposed to appear fifth in the first day’s lineup. But with the scheduled opener, the folk-rock band Sweetwater, nowhere near the stage, festival co-producer Michael Lang had to find a substitute fast—and he had to be able to fit the entire band and its equipment in a small Bell 47. That left Havens. “I said ‘Don’t do this to me, Michael; I’m only one guy,’ ” Havens would relate to Joel Makower in Woodstock: The Oral History. “My bass player isn’t even here.” (He was walking along the highway; after trekking 28 miles, he arrived just as Havens finished his set.)

Not everyone was thrilled to see a Huey overhead. The helicopters persuaded concertgoer Diana Warshawsky to leave. “It seemed more like a war zone that happened to be peaceful at the moment,” she told Makower in 1989. “There was no question about the fact that I wanted to leave.” Author and festivalgoer Susan Reynolds recalled in 2011 the crowd became angry and paranoid when it saw the helicopters. “Was the government there to spy on us, threaten us, disband us, gas us?” Fortunately, someone made an announcement from the stage, which calmed the crowds: “[The Army is] not against us, they are with us, they’re here to give us a hand.”

A small number of helicopters had been used while the site was under construction, and for conducting aerial surveys ahead of time. But they were not meant to be part of the festival, says Chris Langhart, who was the technical director of Woodstock. “I didn’t plan on the road getting stopped up as soon as it did,” he said in a phone interview. “I could see the occasional helicopter dropping someone at the site. But then the roads clogged up, because [the festival basically became] the second largest city in the state of New York. John [Morris, production coordinator at the festival] told his wife to dial up all the helicopters you could find. I think that in the end we had as many as 22, almost all of them from private companies.”

As thousands of people flooded to the site the day before the festival began, a heliport was quickly cleared off, mowed, and constructed adjacent to the performers pavilion, which had a bridge to the stage. That was “about where you wanted it,” says Langhart, “except that it hadn’t been on the original plan. And that was a big error on my part, because those helicopters make a lot of noise” that made it hard to interview performers in the pavilion. “There would have been a very nice set of stories we couldn’t have because of the noise. But I couldn’t have [the musicians] trooping over the field, and that was my only secure area, so it was where it was.

“We needed some way to demarcate it so idiots—performers included in the word ‘idiot’ sometimes—didn’t just walk into the area,” he recalls. “We had a lot of snow fence left, so we made a big rectangle. Then it turned dark, and it turned into ‘We can’t see where the place is’ problem. So we put red Christmas tree lights around the heliport so you could see where it was. And that shows up in the movie also, if you can find the right shot.”

Among the aircraft used at Woodstock were Sikorsky S-58s, which brought performers to the stage and airlifted approximately 250 concertgoers from the site. Helicopters dropped flowers over the crowds, and Army helicopters from West Point delivered more than 1,300 pounds of food, including 10,000 sandwiches prepared by folks in the nearby communities. (Pilot Clark Stahl, who had recently returned from Vietnam, was on temporary duty at West Point when he got the assignment. “What the hell is a rock festival?” he recalled asking another pilot.) Rock photographer Bob Gruen recalls that the Air National Guard “brought in huge barrels of lamb that had been marinated to make shish kebab, and they started giving it away to anybody who had pots and the ability to cook it.”

Chris Langhart never got to see the crowds from the sky; “I saw them from the movie,” he recalls. What was meant to be a small three-day festival would go on to influence an entire generation and become one of the iconic events of the 1960s. And when Richie Havens, the festival’s opening act, died in 2013, his family had one request: that his ashes be scattered by helicopter over the field where the festival took place.