The show features frescoes, preserved fruit, cooking utensils and vessels recovered from Pompeii

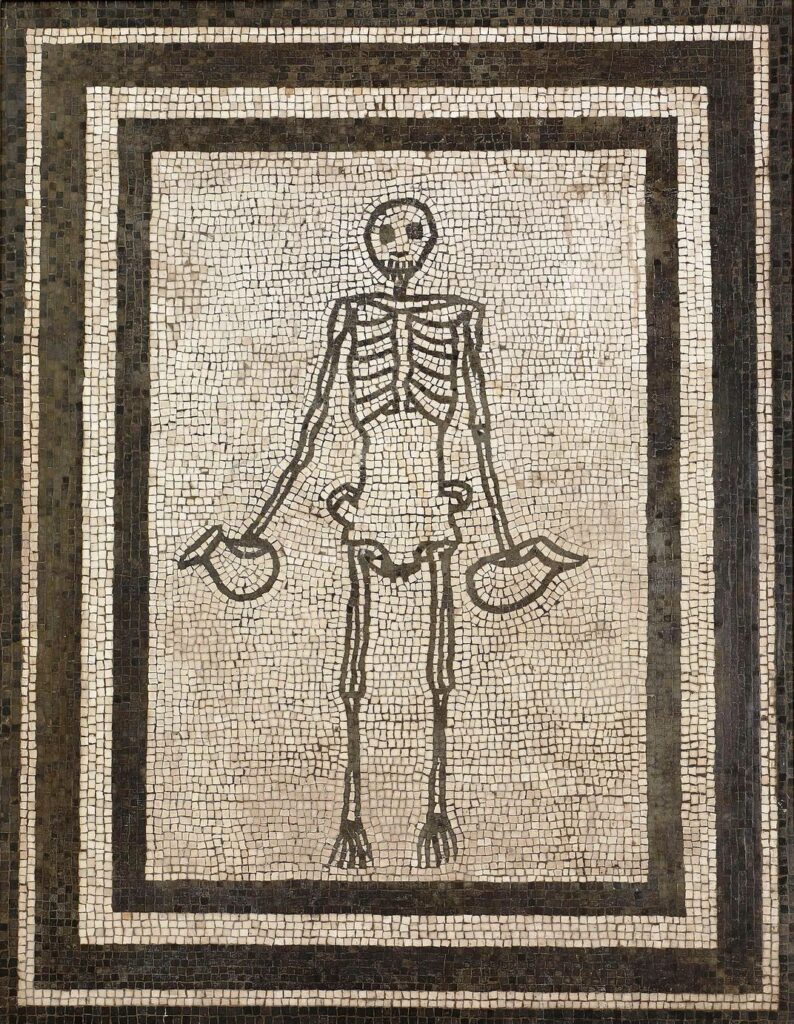

At the House of the Vestals in Pompeii, feasts were punctuated by an eerie reminder of one’s mortality: namely, a monochrome floor mosaic depicting a skeleton carrying two wine jugs. Alluding to the Latin phrase memento mori, or “remember you will die,” the artwork encouraged diners to indulge in earthly pleasures while they still had time—a warning, of course, made all the more prescient by the ancient city’s eventual fate.

Last Supper in Pompeii, a new exhibition at the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, draws on more than 300 artifacts, including frescoes, silver dinnerware, cooking utensils and carbonized bread recovered from the archaeological site, to explore the Romans’ indulgent relationship with food and drink.

Using Pompeii as a starting point, the show traces the wider trajectory of the Roman Empire’s culinary traditions, from delicacies introduced by other cultures to the incorporation of food in religious practices and the tools required to prepare the meals. Last Supper in Pompeii also seeks to demonstrate the centrality of dining in Romans’ everyday life; as exhibition curator Paul Roberts tells the Times’ Jane Wheatley, feasts brought people together while providing a chance for hosts to show off their status through sumptuous decorations, furnishings and foodstuffs.

“Our fascination with the doomed people of Pompeii and their everyday lives has never waned,” says Roberts, who also curated the British Museum’s blockbuster 2013 exhibition, Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. “What better connection can we make with them as ordinary people than through their food and drink?”

According to the Telegraph’s Alastair Sooke, the exhibition also serves to debunk myths surrounding the Romans’ dining habits. But only to an extent. While flamingos and parrots, as well as live birds sewn in pigs, weren’t really typical treats, dormouse—fattened up with acorns and chestnuts, stuffed, baked, and seasoned with honey and poppy seeds, as Mark Brown reports for the Guardian—regularly made the menu.

Other favorites included rabbits stuffed with figs, mousses molded into the shape of chickens, focaccia bread, pomegranates and grapes. To garnish these and other delicacies, Pompeiians relied on garum, a fermented fish sauce that the poet Martial described as a “lordly, … costly gift, made from the first blood of a still-gasping mackerel.”

Per the Times’ Wheatley, the carbonized food excavated from Pompeii is a particular highlight of the exhibition. Among others, the trove features olives, eggs, figs, carob, almonds, lentils and a loaf of bread sliced into eight pieces.

Also of note are the artifacts staged to make visitors feel as if they have stepped back in time to 79 A.D., the year of Mount Vesuvius’ devastating eruption. As the Telegraph’s Sooke reports, Last Supper in Pompeii weaves through the city’s double-storied streets, accentuated by a fresco advertisement for a local bar and a bronze statue of a street hawker, before arriving in the atrium of a wealthy resident’s home. Inside the triclinium, or formal dining room, more frescoes, mosaics and artwork await alongside silver cups for dinner guests, intact glassware, bronze vessels and a blue-trimmed bowl. Thirty-seven vessels included in the display underwent conservation specifically for the exhibition.

Past the triclinium, museum visitors will find, in Wheatley’s words, the “small, dark and smoky” room where cooking took place. Oftentimes, kitchens—populated by enslaved workers tasked with using steam cookers, colanders, molds, roasting trays and other utensils to prepare meals—were situated right next to the latrine; needless to say, they were hot, dirty and deeply unhygienic.

While the people enjoying these elaborate feasts were those in the upper echelons of society, as Bee Wilson explained for the Telegraph in 2013, poorer Pompeiians didn’t fare too badly when it came to food; the average Joe regularly dined at the city’s roughly 150 “fast food” restaurants, or thermopolia. (In April, Smithsonian’s Jason Daley wrote about how archaeologists working on the Great Pompeii Project unearthed an elaborately painted thermopolium, one of more than 80 recovered to date.)

Last Supper in Pompeii closes with a nod to the destroyed city’s inhabitants, as represented by the so-called “resin lady” of Oplontis. Presumably a member of the wealthy family that owned Pompeii’s great emporium, she was found in the building’s storeroom alongside 60 other Vesuvius victims. The possessions she held during her final moments—gold and silver jewelry, a string of cheap beads and a key—were abandoned nearby.